Whitepaper

Fair Fees and Alignment – Building Long-Term Partnerships with Best-In-Class Asset Managers

30 September 2019

In 2014 we wrote our first whitepaper on “the war on fees”. At the time the proliferation of low-cost passive investment options was challenging the traditional high-fee model of active management. Alignment was poor, and many asset managers generated significant personal wealth regardless of whether they delivered excess returns for their investors. Over the last five years, increased pressure from large institutional investors like Partners Capital has resulted in significant improvements across the industry with increasingly creative fee structures designed to improve alignment between manager and investor. For example, performance fees are now increasingly paid on excess returns rather than on market returns. While there is no simple answer on the “right” fee structure and each situation is unique, we have developed six core principles for fair and aligned fee structures. These should provide a pragmatic and practical framework to navigate this challenging topic, and engender more resilient long-term partnerships between asset owners and asset managers.

The Current Environment for Asset Manager Fees

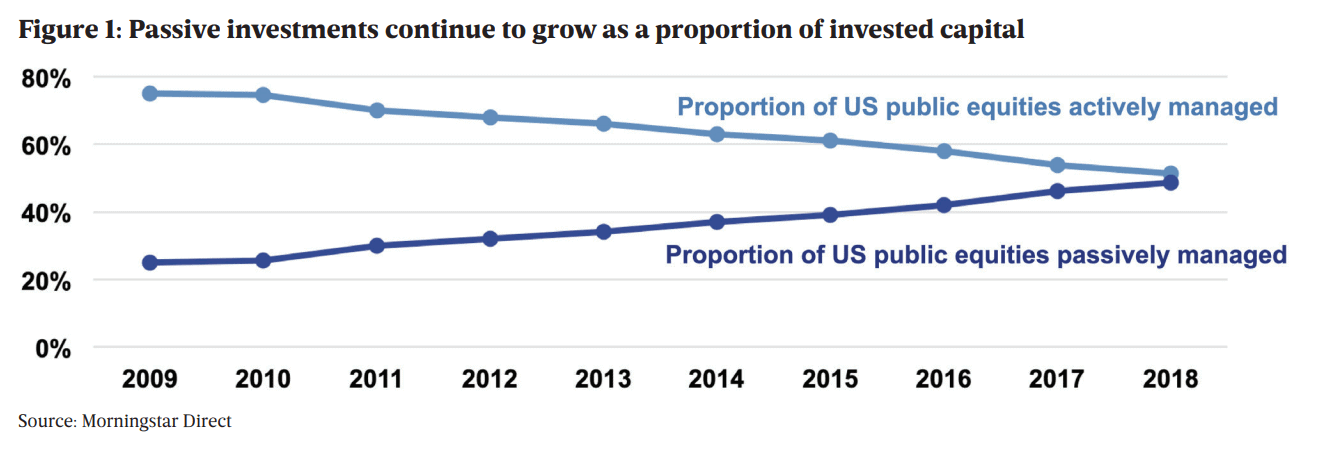

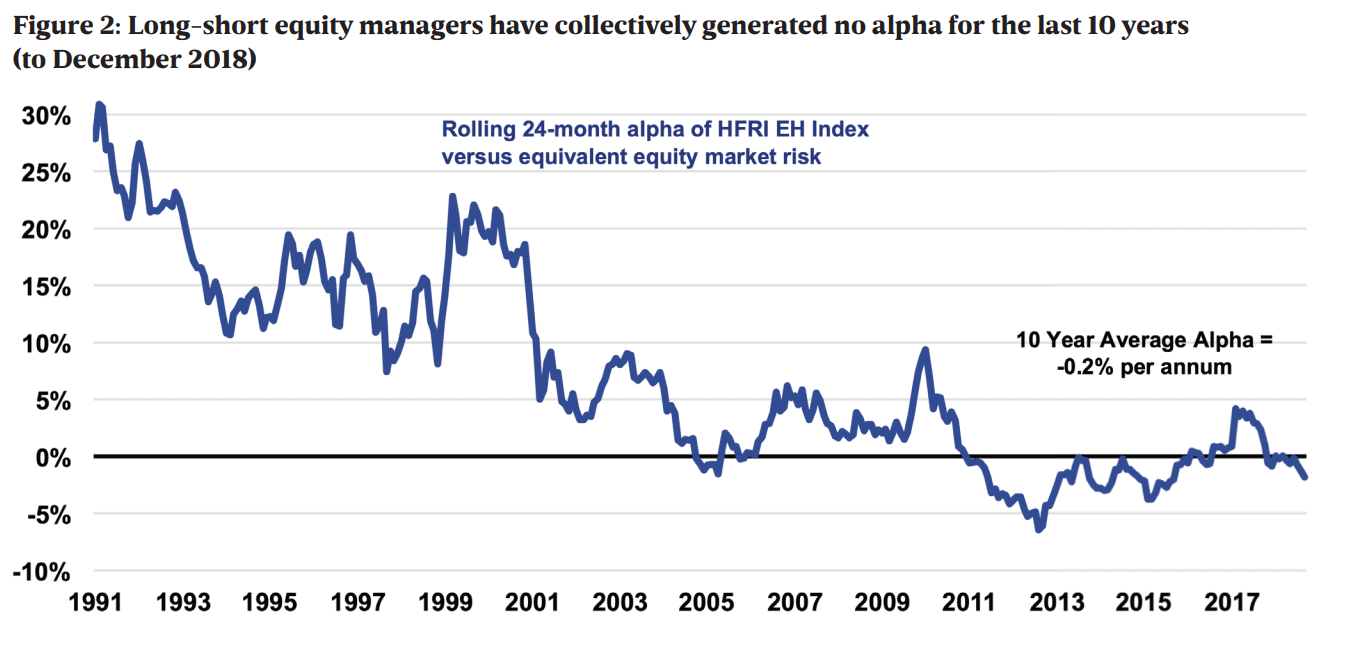

Over the last few decades two factors have driven a seismic shift in the competitive dynamics in the asset management industry: the dramatic increase in passive investing and the continuing decline of excess returns produced by the asset management industry. When John Bogle first launched an S&P 500 tracker with Vanguard in 1976, he raised $11.3 million in assets, well short of his $150 million target. Since then, we have seen an explosion in the availability of passive investment options, and a dramatic reduction in their costs. The expense ratio of Vanguard’s S&P 500 tracker has declined by c.90% from over 0.4% in 1976 to just 0.04% today. These pricing trends are increasingly evident in the Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) market which has undergone a price war over the past five years with Vanguard, Blackrock and Charles Schwab all aggressively reducing their fees to attract and retain business. At the same time as the passive investing revolution, we have also seen a trend of declining alpha over the last decade, particularly in alternative asset classes.

The decline in hedge fund alpha is exemplified by comparing returns of the long-short equity hedge fund index against a risk-equivalent equity benchmark. The conclusion is stark: there has been effectively no alpha in the last 10 years.

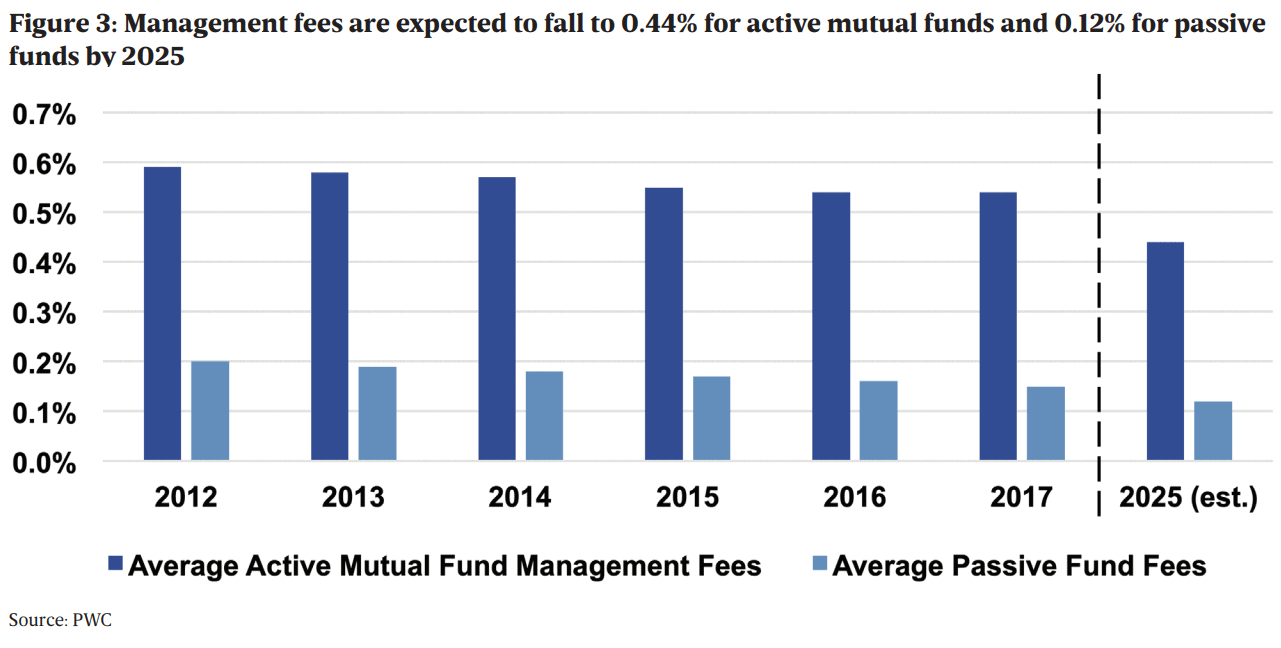

These major shifts in the investment landscape have fundamentally altered the dynamics of the asset management industry. As a result, we are seeing continued momentum towards lower fees in the investment world, across both traditional and alternative assets. As seen in Figure 3 below, PWC forecast fees to continue declining for both active and passive mutual funds by approximately 20% over the next 6 years. PWC estimate that average fees for active mutual funds will decline from 0.54% to 0.44%, and from 0.20% to 0.12% for passive funds by 2025.

In some cases this reduction in fees has been taken to an extreme. In 2018 Fidelity announced the launch of two no-fee funds, which has since increased to four. These include the Fidelity ZERO Total Market Index Fund which offers exposure to 2,500 stocks in the United States, a large cap fund, an extended market fund and an international index fund. While these are loss-leaders which require the usage of a Fidelity brokerage account, they reflect the continued pressure on industry fees.

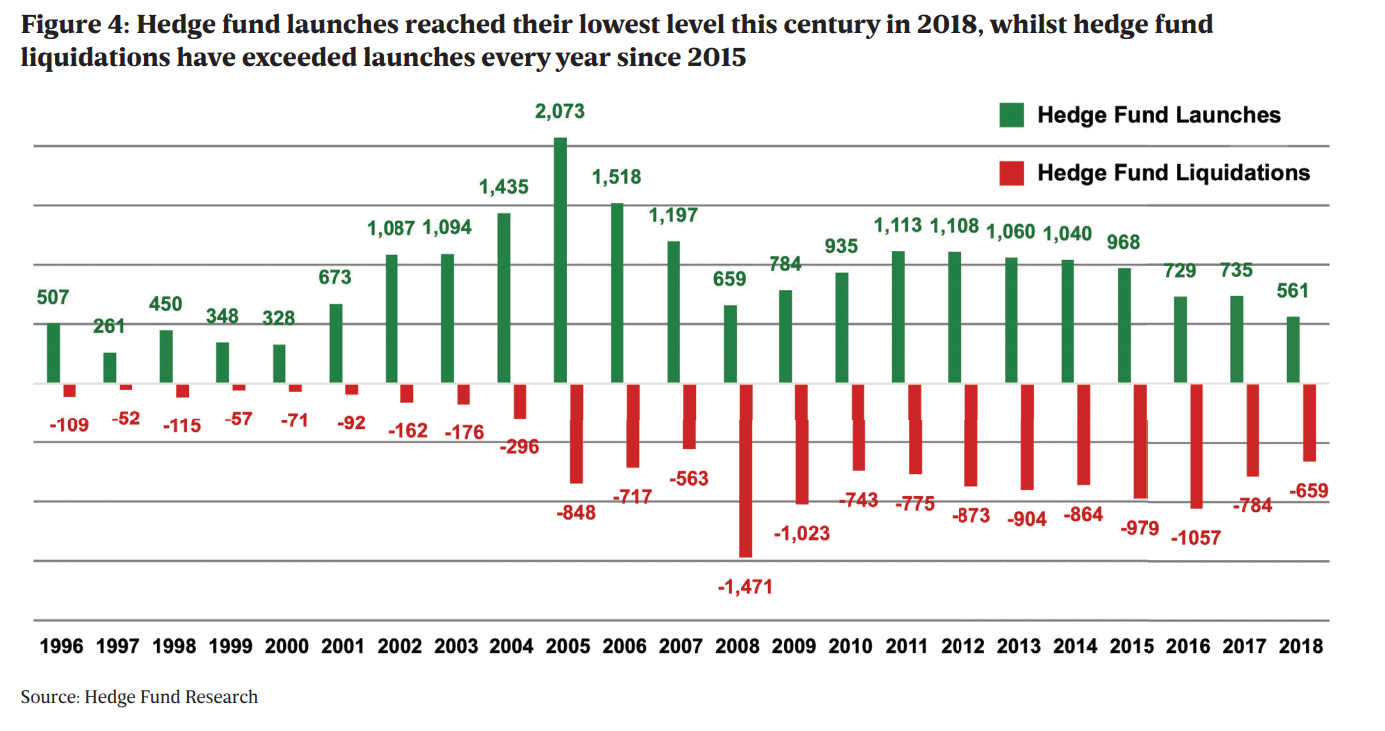

Far from being the so-called “Masters of the Universe” that they once were, hedge funds are also under increasing pressure as market forces drive non-economic players out of the industry. New hedge fund launches, according to HFR, reached their lowest level this century in 2018 with only 561 new launches. This compares to 735 the previous year and a peak of 2,073 in 2005. Meanwhile, hedge fund liquidations have exceeded launches every year since 2015.

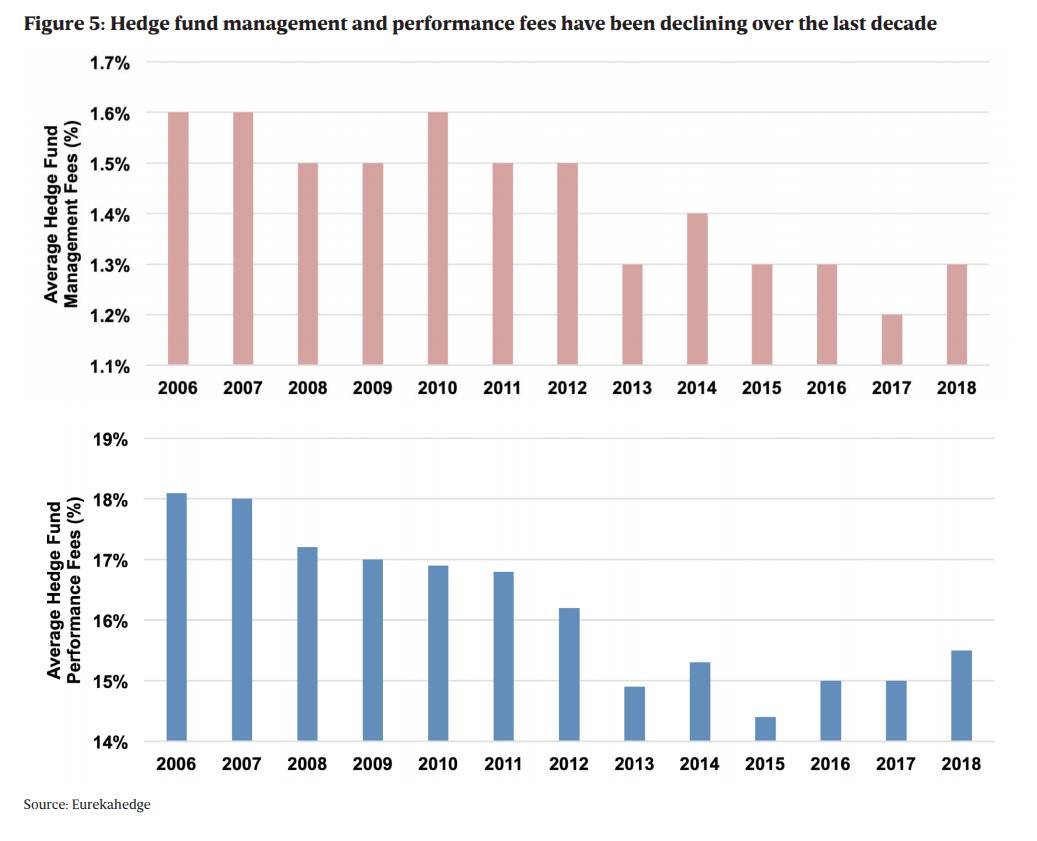

Fees in the hedge fund industry have been declining meaningfully over the last decade across both management fees and performance fees as a result.

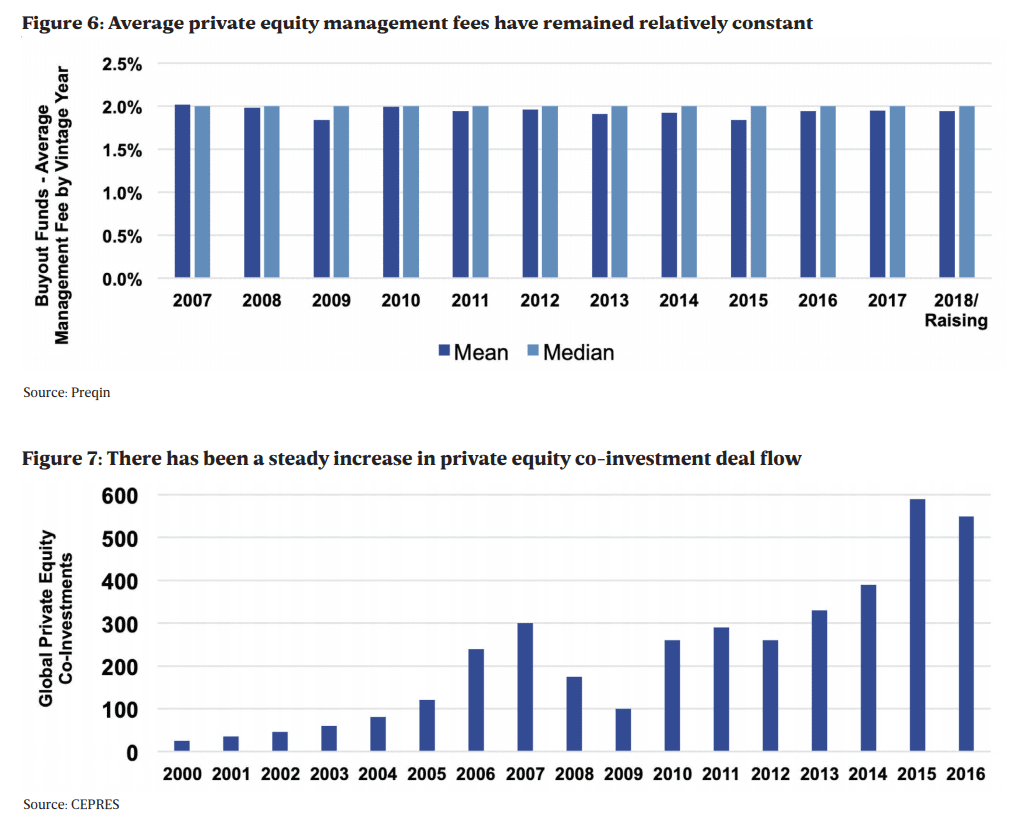

However, the dynamics for investors in private markets are not so favourable, as headline fees have not experienced the same downwards pressure. Given the continued flood of capital chasing private equity, headline management fees have remained remarkably constant over this period with the median fund continuing to charge a 2% management fee, and the mean fund charging close to 2%. In private equity, a Preqin survey between 2013-2016 revealed that over a third of LPs did not feel that GP and LP interests were properly aligned, with the top three areas for improvement cited as management fees (67%), the structure of the performance fee (58%) and the amount of the performance fee (48%).

As headline fees in private equity remain sticky, we have seen many asset managers reward their largest and most strategic investors with low-fee or fee-free co-investment opportunities. This is equivalent to a fee reduction for investors, and more importantly helps to further cement the relationship between investor and asset manager.

Partners Capital Principles on Manager Fees

We welcome these market developments, particularly the reduction in the absolute level of fees charged and the increasing availability of low-cost passive investments. However, we continue to push managers to rethink their approach to fees. Fair fees and alignment will help to engender long-term and mutually beneficial partnerships between asset owners and asset managers.

Our approach to fees can be summarized in six principles:

1. Management fees should not be a source of wealth creation for asset managers.

2. Performance fees should only be charged on excess returns, with investors getting a fair share of those excess returns.

3. Not all capital is created equal – reward your best investors.

4. Fee structures should be simple and transparent.

5. Don’t throw the alpha baby out with the fee bathwater.

6. Seek co-investment opportunities to lower the overall fee burden.

Principle 1: Management fees should not be a source of wealth creation for asset managers

Asset management companies are extremely high margin businesses with enormous operating leverage. It is well-documented that money management is the source of wealth for some of the richest people on earth. Although set-up costs are often high due to the regulatory, technological and hiring requirements of an asset management business, once a firm is stable and generating profits, the margin on incremental assets is typically very large. We recognise that the economically-rational strategy for an asset manager (at least in the short term) is to gather assets and earn the recurring management fee rather than to focus on outperformance. However, successful asset gatherers and marketers are too often confused with successful investors.

Our view is that management fees should exist only to cover the operating costs required to run the business and to attract and retain exceptional talent. Several thoughtful solutions exist to remedy this misalignment of incentives, but we increasingly see managers whose management fee decreases as assets increase, to reflect the reality that incremental assets earn exceptionally high margins once the business has covered its costs. This engenders incredible long-term loyalty from investors.

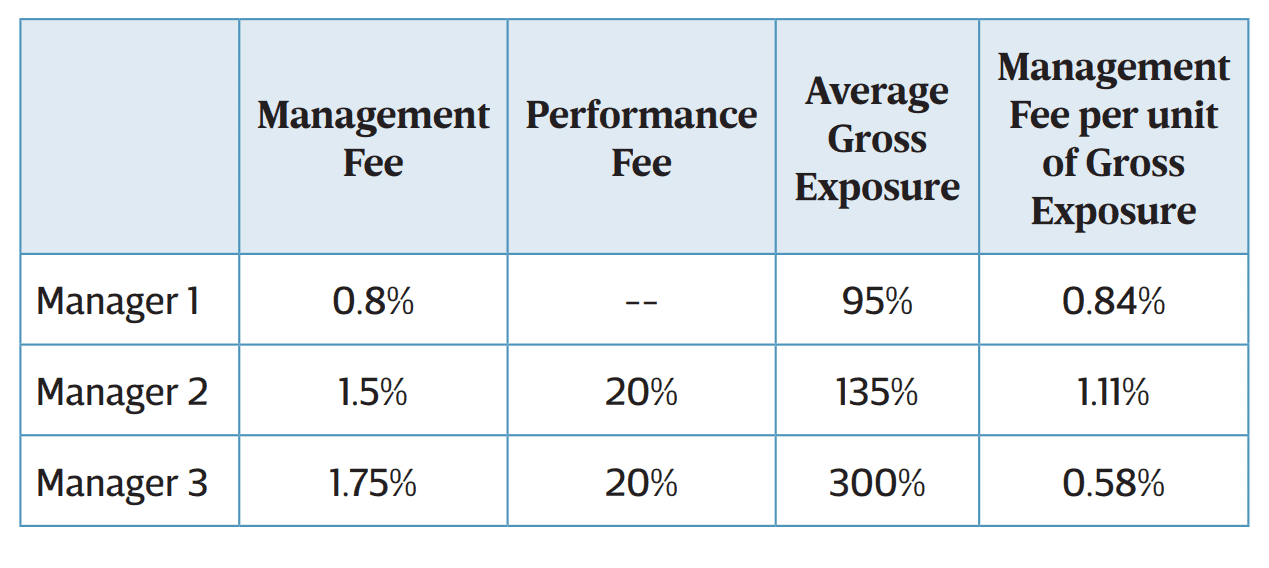

From an investor’s perspective, a helpful framework for considering value-for-money on management fees is to determine the management fee charged per unit of gross exposure, or the notional value of long and short investments. Below, we compare 3 managers with different fee regimes and differing levels of gross exposure. At a superficial level, one may conclude that Manager 1 offers the best value-for-money as they charge the lowest management fee and no performance fee. But for Manager 3, if we consider the fact that we gain $3 of gross exposure for every $1 we invest in the fund, we may conclude that it offers the best value-for-money as the effective management fee per unit of exposure is the lowest at 0.58%. Although the manager is earning more in management fees per dollar invested by the investor, the investor may well be getting more “bang for their buck”.

Figure 8: Assessing management fees per unit of gross exposure can provide a helpful framework for considering value-for-money

Principle 2: Performance fees should only be charged on excess returns, with investors getting a fair share of those excess returns

Most actively managed investment products bundle together market returns (beta) and excess returns (alpha). Because the average investor lacks the sophistication to separate returns attributable to skill from market returns, this bundling results in higher fees than the investor should otherwise be willing to pay. The hedge fund industry has been slow to introduce more innovative alpha-based fee structures.

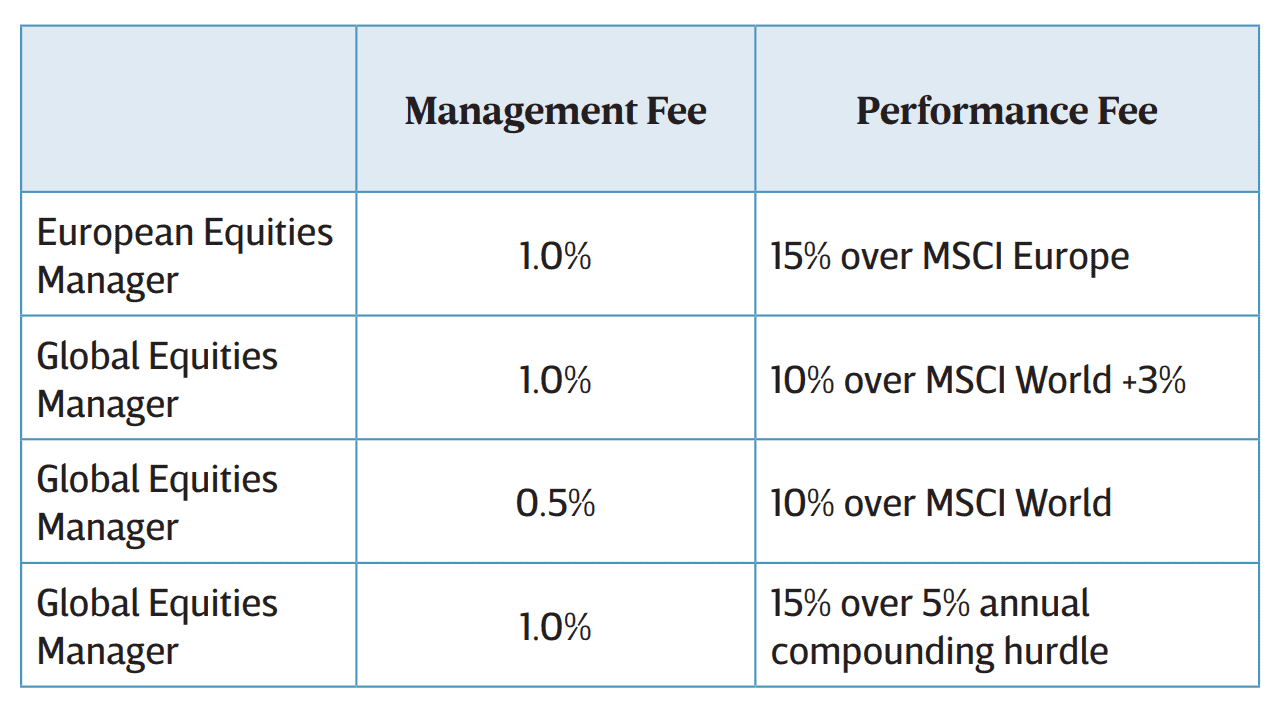

We have seen some progress on this front in new launches of long-only equity funds. Many equity long/ short hedge fund firms have launched long-only offerings in recent years, driven by investor appetite and the elusiveness of alpha from the short side of the book. As shown in Figure 9, we have seen several examples of these funds offered with a lower base management fee than the equivalent long/short fund and performance fees paid only on outperformance above a market benchmark.

Figure 9: We see an increasing trend towards alpha-based performance fees

Over the last few years, we have developed a measure of the value-add delivered by a manager relative to the fees that they charge. We refer to this as Excess Return on Cost (EROC), and it is calculated as the ratio of gross alpha to total fees charged.

This ratio reflects how alpha, or excess returns, are shared between investor and manager. For example, an EROC ratio of 2x would equate to a manager delivering $2 of pre-fee alpha for every $1 of fees paid (in other words, the manager keeping 50% of their gross alpha in fees). Likewise, an EROC ratio lower than 0 implies that the manager has not delivered any alpha, even before their fees. Meanwhile, an EROC ratio between 0 and 1.0x implies that the manager’s fees exceed any gross value added (i.e. the manager generates some gross alpha, but this is more than offset by their fees). The inverse of the EROC measure equates to the percentage of alpha consumed by a manager’s fees.

We consider the minimum acceptable EROC for a manager to be 2x, which means the investor keeps at least half of the gross alpha generated by the manager. We work with our asset managers to design innovative fee terms which align incentives appropriately, and only reward returns in excess of market performance or absolute targets reflecting an appropriate cost of capital.

Historically, it was not uncommon that an exceptional long-only equities manager could charge a “2 and 20” fee arrangement under the premise (and promise) of exceptional returns. This fee structure is very difficult to analyse prospectively using an EROC framework, as the performance fees would be determined by the performance of the equity market as much as it would be by the excess return generated by the manager. If we assume this manager can deliver 5% alpha in excess of the equity market, they would be charging 6.6% if the equity market returned 20% (i.e. their fees would exceed their alpha for an EROC of 0.76) but 2.6% if the equity market returned zero (i.e. their fees consume approximately half their alpha for an EROC of 1.92). We strive to create fee structures which produce a fair split of alpha in any market environment. For instance, we were successful with one manager in negotiating a “0 and 40” fee structure, with the 40% performance fee only charged on returns in excess of the manager’s benchmark. This arrangement guarantees an EROC of 2.5x, provided the manager produces positive alpha.

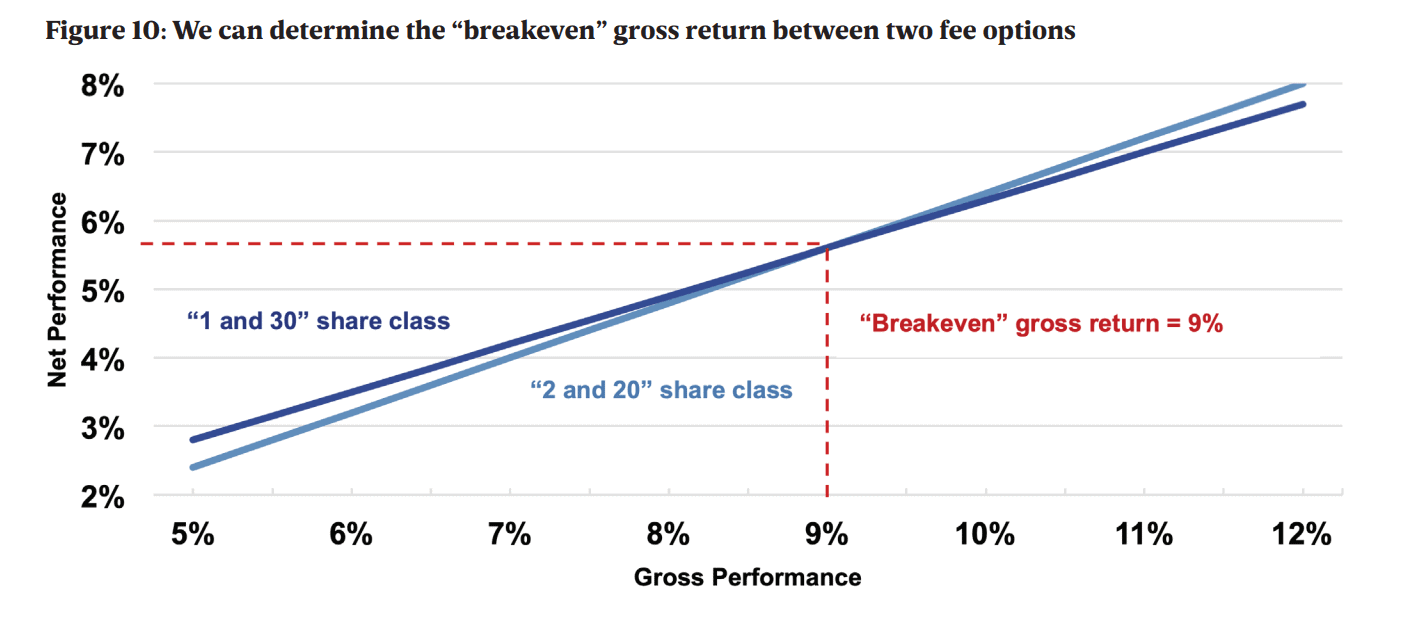

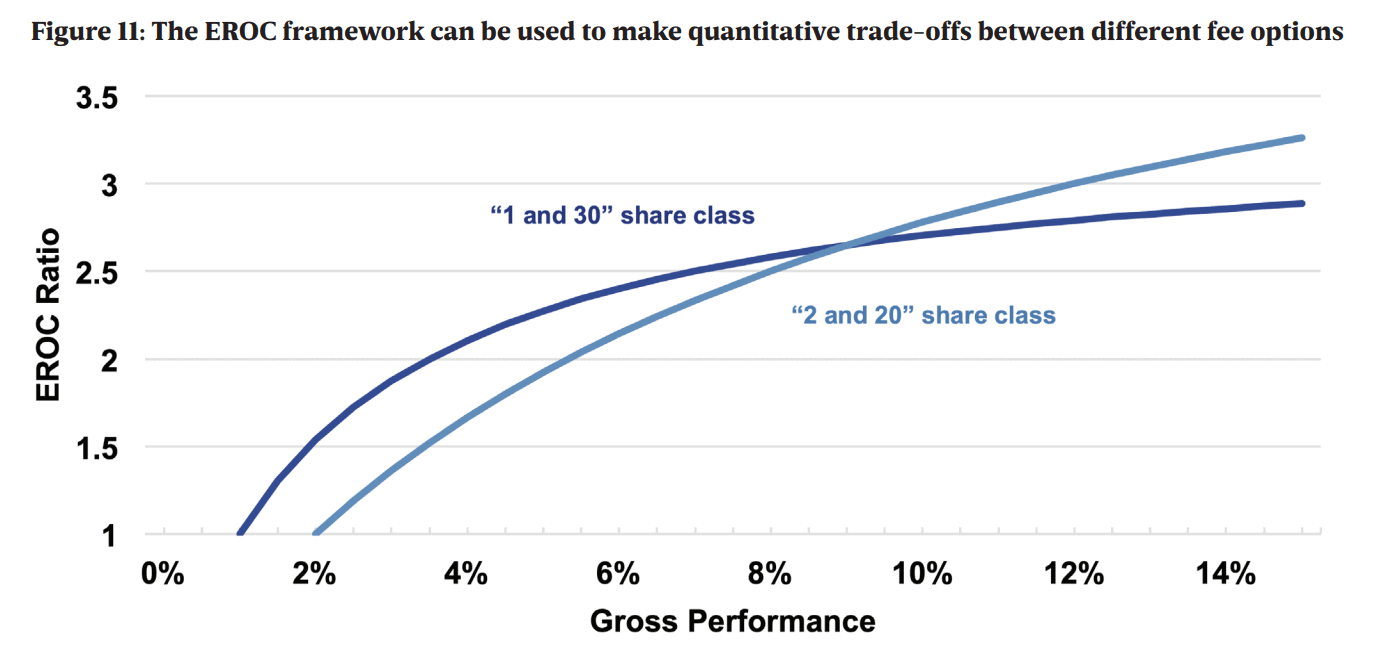

Similarly, we make use of the EROC framework when making trade-offs between different manager share classes. We invest with one absolute return manager who offers investors the option of a “2 and 20” or a “1 and 30” fee arrangement. The framework allows us to make quantitative trade-offs between different fee options offered by managers. In Figure 10, we conclude that the investor is better off with the “1 and 30” option provided the manager’s gross returns are below 9.0%. In Figure 11, we conclude that for the “2 and 20” fee arrangement, the EROC ratio only exceeds 2.0x if the manager’s gross returns exceed c.5.4%, while for the “1 and 30” option, the EROC ratio exceeds 2.0x if the manager’s gross returns exceed 3.5%. As we are generally sceptical of alpha, we like the added alignment of a lower management and a higher performance fee. Indeed, a recent survey by AIMA in July 2019 revealed that nearly 80% of managers would reduce management fees in return for a greater share of performance.

Just as we can evaluate a manager’s value-add as a ratio of their fees, our clients can also evaluate Partners Capital’s value-for-money using an EROC-style framework. Whilst we set a minimum target EROC of 2x for asset managers, we target an EROC ratio of 2-3x for our clients on our fees. One can measure Partners Capital’s EROC by taking the ratio of manager alpha and tactical asset allocation alpha we deliver before fees and dividing by the fees we charge.

One key question is whether 50% truly represents a fair split of alpha between investors and managers. It is believed the “2 and 20” fee model originated in the early 19th century as the incentive structure paid to agents who funded risky whaling expeditions in North America. Whilst it is understandable that such risky ventures required significant reward as compensation, it is less clear that the money management industry should be as handsomely rewarded given the estimated $300 billion of fees earned by the asset management industry each year.

We have concluded that 50% represents a suitable minimum threshold for the split of alpha between the asset manager and the asset owner, less as a view as to the “fair” split of alpha but more as an expression of the margin of safety we require to compensate for the uncertainty inherent in any forward-looking estimate of manager alpha. We can think of no fundamental justification as to why 50% represents a “fair” split of alpha, but nor could we justify any division of alpha as either “fair” or “unfair”. The AIMA survey also revealed that “discussions with managers and investors during the research reveal a shared belief that managers’ share of alpha should be about one third”.

We have recently seen interest from some clients, particularly fiduciaries of institutional pools of assets, for an overall portfolio-level fee cap. This can manifest either as a cap on fees that can be paid to third-party managers, or constraints on a portfolio such as a minimum allocation to managers below a certain fee threshold. In some asset classes, particularly more efficient asset classes such as global equities or fixed income where alpha is so elusive, it is tempting to focus purely on minimising fees. We sympathise with this line of argument, but do not recommend such an approach. We must remember that alpha does not have a floor of zero, and a focus solely on minimising fees and costs may lead to adverse selection. Sometimes you get what you pay for.

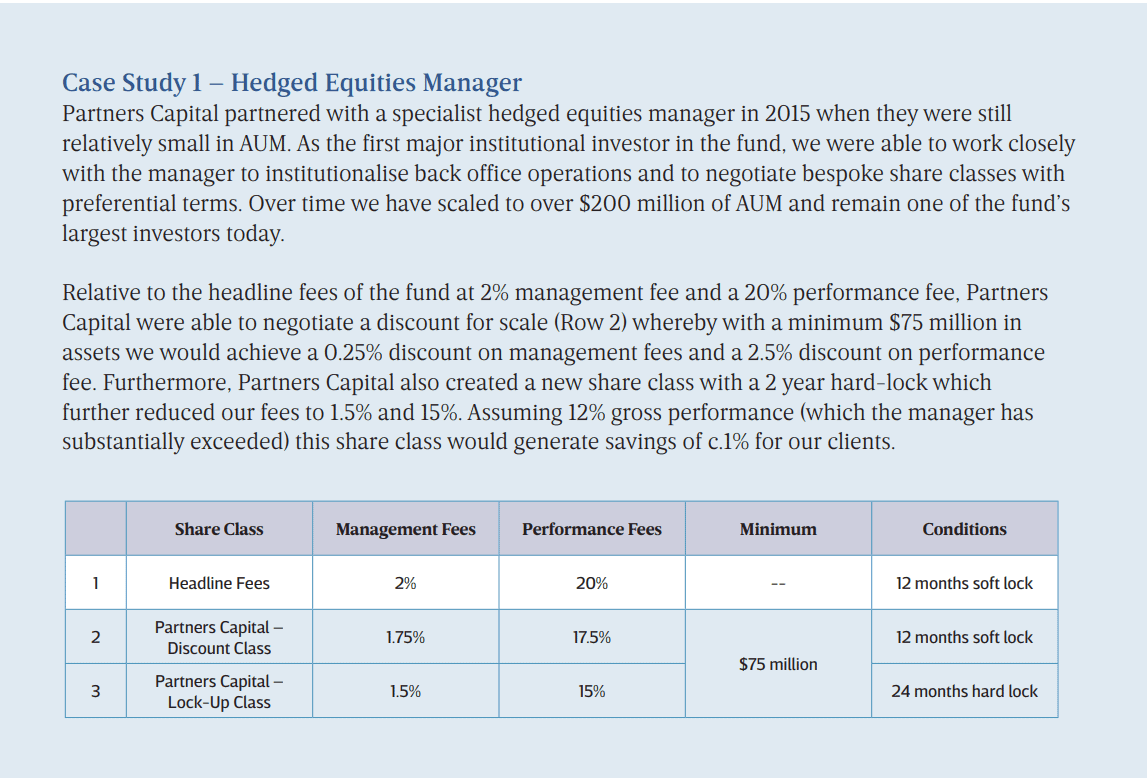

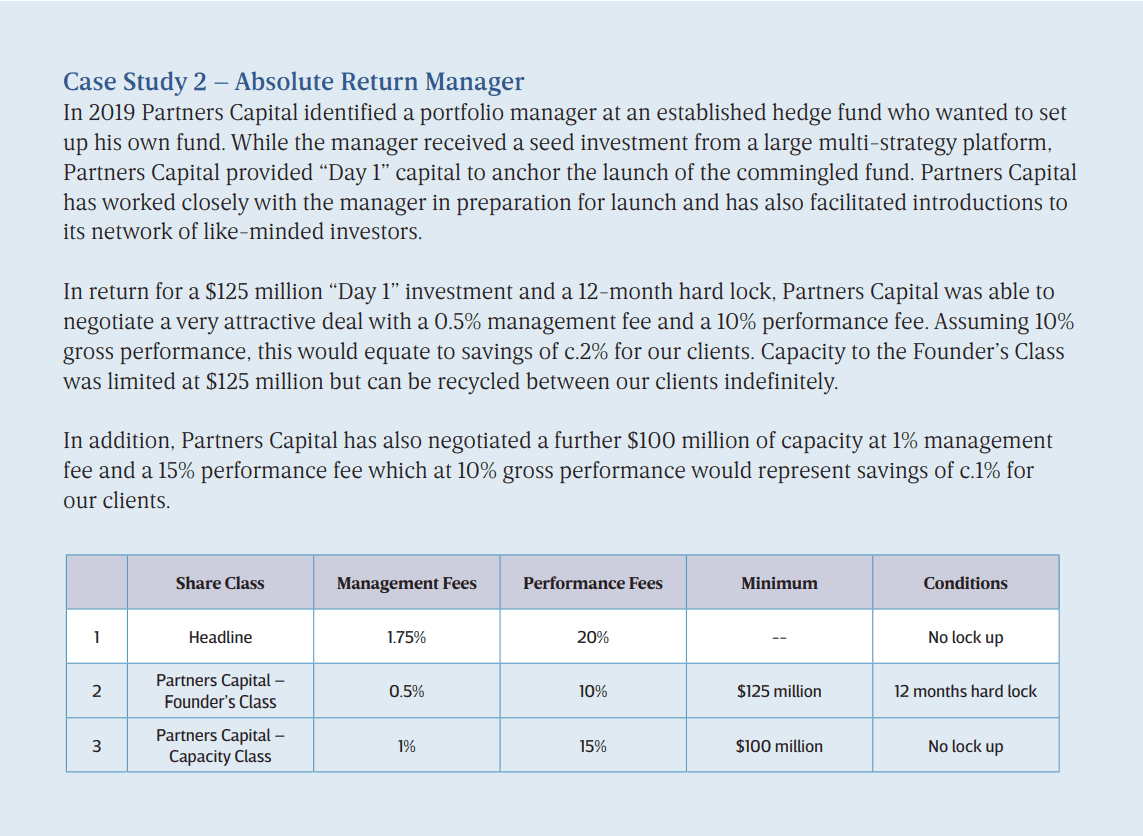

Principle 3: Not all capital is created equal – reward your best investors

Just as not all managers are created equal, not all investors are created equal. We encourage asset managers to focus on the quality of their investors and to use fee structures to create long-term alignment and partnership. We believe that investors should be rewarded with fee discounts for being early, for being large and for being illiquid:

- Being early. Investors who take greater risks early in the fund’s or strategy’s life should be rewarded. This can be through founders’ share classes, first-close discounts or GP economics in the case of a seeding deal.

- Being large. Larger investors should be rewarded relative to smaller investors. One $100 million relationship is far more efficient to manage than ten $10 million relationships or one hundred $1 million relationships.

- Being illiquid. Investors who are willing to commit their capital for a longer duration should be rewarded for duration of capital.

Below, we show three case studies where we have been able to negotiate meaningful discounts for our clients.

Principle 4: Fee structures should be simple and transparent

We believe that a simple fee structure is preferable to a more complex one. Although additional safeguards can often be beneficial to investors and managers alike even if they add some complexity, our overriding principle is to select fee structures which are easily comprehensible and calculable to promote the overall goal of alignment of interests. Managers should avoid negotiating overly complex fee arrangements as these can prove to be significant distractions from their investment responsibilities.

Another key aspect of this principle is transparency. Managers should be transparent with the fees they charge, and to other investors about what fees other investors are paying. We dislike complex, confidential sideletter agreements which are a significant distraction for management and prevent other LPs from understanding how the manager is incentivised. We believe that investors who are early should be rewarded, but otherwise are happy for the scale and duration discounts that we negotiate to be made available to all investors.

Principle 5: Don’t throw the alpha baby out with the fee bathwater

There is one thing we should be completely clear on: Partners Capital has no objection (moral or otherwise) to high asset management fees per se. Indeed, we happily pay fees for outperformance. We have many examples of managers to whom we gladly pay high fees, provided they are sensible in proportion to alpha generated.

Although we would always prefer for our clients’ fee load to be lower, our primary concern is to ensure that managers are adequately incentivised and compensated to deliver against their alpha objectives. Our key consideration as rational investors is net-offees return and, although sometimes the absolute fee load may seem unpalatable, we should be prepared to pay high fees provided it is commensurate with the net-of-fee alpha accruing to the portfolio.

For us, good alignment and a fair share of alpha is of greater importance than the absolute fee level. This promotes a culture of positive, cooperative partnership that we seek in our manager relationships. All managers will ultimately experience a period of underperformance, and partnerships which had demonstrated alignment at the outset will naturally earn greater loyalty and patience from their investors.

Principle 6: Seek co-investment opportunities to lower the overall fee burden

In addition to pushing for equitable changes to managers’ fee schedules, institutional investors increasingly target fee-free or reduced-fee co-investment opportunities across a range of asset classes including private equity, private debt, and public equities. It has become the rule, rather than the exception, that large institutional investors negotiate access to fee-free direct private equity co-investment opportunities. This is tantamount to a fee reduction for larger investors in private equity funds and the effective fee discount can often be as high as 50% assuming a 1:1 fund to co-investment ratio. This is a major strategic priority at Partners Capital. In 2019 we launched the Merlin Fund, our first pooled vehicle dedicated to private markets co-investments, with $150 million of commitments.

Co-investment has also extended into the realm of public securities. A growing number of large institutional investors manage in-house public equity co-investment programs where they effectively replicate the top holdings of their core equity managers. Successful replication requires managers who generally invest with long holding periods and where trading alpha is not a major source of outperformance. At Partners Capital, we launched a public equities co-investment program in 2013 which has now grown to over $1.2 billion in assets.

Conclusion

We hope that this whitepaper provides both investors and managers with some frameworks and tools to foster a pragmatic and healthy debate on fees in the asset management industry. Although

every investor would like their managers to generate high alpha at low cost, we accept that the best managers are able to, and should, charge a premium for their skills. Our focus is on achieving fair fees and alignment so that asset owners and managers can build successful long-term partnerships.

We accept that our thinking will continue to evolve, as it has done since we published our first whitepaper on the subject in 2014, and look forward to updating you on our progress.