Newsletter

Inflections: Trump 2.0 Tariffs: ‘Art of the Deal’ or ‘The Most Beautiful Word’?

5 December 2024

Although there is still over a month to go before inauguration, the new Trump cabinet has largely taken shape and a slew of major policy shifts have been announced. Trade policy is front and center with investors trying to guess whether the threat of tariffs will be primarily used as a negotiating tool to exact concessions, a scenario we refer to as ‘Art of the Deal’, or as an end in themselves, our ‘Tariff is the Most Beautiful Word’ scenario.

In the latest edition of our Partners Capital Inflections series, we share our thinking on these scenarios and evaluate three critical issues related to the upcoming reconfiguration of trade policies. These include: 1) Lessons from history 2) Potential guardrails, and 3) Likely outcomes and investment implications.

The signals from the incoming president have so far been mixed. During the campaign, he threatened up to 100% tariffs on China and 10-20% tariffs on the rest of the world. He then somewhat calmed markets by appointing Wall Street veteran Scott Bessent as Treasury Secretary who suggested that tariffs would be layered on gradually and for well-defined purposes, rather than unleashed all at once. However, the very next day, Trump panicked investors by threatening to impose immediate tariffs of 25% on goods from Mexico and Canada, as well as an additional 10% on China. Collectively, these three countries account for 45% of US imports1. Even more surprisingly, such tariffs would violate the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), a trade deal which Trump himself negotiated in his first term and called the ‘best deal ever’. Investors could be forgiven for thinking a strategy of unpredictability is a goal in itself.

Although there is much uncertainty, the signal from financial markets for now appears to lean towards the more pragmatic scenario of using limited tariffs as a negotiating tool. The very fact that the Mexico and Canada tariff threats were linked to improving controls on immigration and Fentanyl imports, seems to suggest there is room for compromise.

However, there is a credible case that Trump genuinely believes in tariffs as an end in themselves. Tariffs were a key policy plank of his election campaign, were implemented extensively in his first term and were even advocated for in his many interviews dating from his time as a real-estate developer in the 1980s.

Moreover, the appointment of Scott Bessent should not be seen as a vote against tariffs. Bessent has clear views, but the Treasury Department has little power in trade matters. When Trump appointed Bessent’s rival, Howard Lutnick, as commerce secretary, he stated that Lutnick would be in charge of trade policy, and that the US Trade Representative (USTR ) would report to him.

Perhaps most importantly, from a political perspective Trump sits atop a coalition of three broad interest groups, of which the business and financial community represented by Bessent is just one. The others are the economic nationalists such as Robert Lighthizer (former USTR in Trump’s first term), and various national security hawks. Trump’s national security team—Secretary of State Marco Rubio, National Security Advisor Michael Waltz, and Deputy National Security Advisor Alex Wong—all advocate a maximalist line on China, including a large degree of economic decoupling (as opposed to simply balancing trade).

1. Lessons from history: How radical would heavy tariffs be?

Despite conventional wisdom, the use of trade tariffs by the United States as the bastion of free market capitalism is not unprecedented or even uncommon. Those investors today whose frame of reference spans the post-WW2 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) era, and particularly the post-1995 World Trade Organisation (WTO) era, often think of tariffs as a novel phenomenon introduced in the first Trump term.

US economic history over the last 200 years reveals frequent bouts of large-scale tariffs

- While ostensibly aimed at improving domestic economic competitiveness, these policies often resulted in sub-optimal economic outcomes, and occasionally even precipitated geopolitical crises.

- In the mid-19th century, tariffs accounted for about 90% of federal revenue, according to the U.S. International Trade Commission. The Tariff Act of 1828 imposed rates as high as 50% on imported goods. These were primarily aimed at British goods to protect manufacturers in the Northeast and Midwest. However, the more agricultural Southern states, heavily dependent upon cotton exports to Great Britain, branded them “Tariffs of Abominations.” Southerners not only saw a drop in export income due to retaliation by trading partners but also had to purchase goods from the then-nascent manufacturers in the Northeast for higher prices than from the advanced British industrial machine. This rift led to deep political tensions. Combined with the lead-up to the Morrill Tariff Act of 1861, these tensions helped lay the groundwork for the Civil War of 1861-1865.

- Following the Civil War, the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 raised the average duty on all imports to almost 50%, an increase designed to protect domestic industries and workers from foreign competition. The tariff was not well received by voters who suffered steep cost-of-living increases. In the 1892 presidential election, the Senate, House, and Presidency all shifted to Democratic control. In 1894, the Wilson-Gorman Act was passed, sharply lowering tariffs.

- In the early 20th Century, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 raised tariffs again on over 20,000 imported goods, leading to a 66% decline2 in global trade between 1929 and 1934. U.S. exports fell from about $5.2 billion in 1929 to $1.7 billion by 19332, exacerbating the Great Depression. GDP growth stagnated, and unemployment surged to over 25%2. The Great Depression, and its outsized impact on Germany in particular, is often listed as one of the major causes of WWII.

Following WWII, trade liberalisation began in earnest

- The US-led establishment of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947 reduced average tariff rates among developed nations from 22% in the 1930s to less than 5%2 by the 1980s. Global trade grew by an average of 6% annually in the same period2.

- The 1957 Treaty of Rome (forerunner to the European Union) was established with the principal goal of preventing the threat of war on the continent by entrenching deep trade links between member countries.

- In 1994, the North American Trade Agreement (NAFTA) eased trade flows between the US, Canada and Mexico.

- The 1995 WTO agreement extended the GATT framework, notably bringing services and agriculture into the fold. China became a WTO member in 2001, a development that contributed heavily to the ensuing two-decade era of disinflation, allowing central banks to reduce interest rates, contributing to economic output and investment gains across asset classes, risky and safe.

21st Century: Resurgent Tariff Use – and the extension of goals to include national security:

- In response to rising imports from China and the coincident (although not necessarily causal) decline in US manufacturing jobs, the first Trump administration imposed nearly $80 billion of new tariffs on thousands of products valued at approximately $380 billion in 2018 and 2019.

- In 2018, Trump proposed replacing NAFTA with a new agreement, the USMCA, tightening rules of origin for automotive parts, and protecting agriculture and IP.

- Interestingly, following the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus of tariffs broadened from pure protectionism goals to also include national security and supply chain resilience.

- The Biden administration kept many of the Trump administration tariffs in place, and in May 2024, announced tariff hikes on an additional $18 billion of Chinese goods, including semiconductors and electric vehicles, for an increase of $3.6 billion according to the Tax Foundation.

- The U.S. Trade Representative estimates that the post-2018 restrictive measures affected nearly 12% of total U.S. imports. Tariffs against China reduced a $375 billion trade deficit with China in 2017 to $310 billion in 2021, although trade tensions persisted. The Federal Reserve estimates that tariffs reduced US GDP growth by -0.3% in 2019 and increased consumer price levels by +0.4%. According to the Tax Foundation, S&P 500 companies reported a $40 billion hit to profits in 2019 due to higher input costs and lost export markets.

2. What, if any, guardrails are there against more extreme tariff outcomes?

Many analysts have posited that the ‘Red Sweep’ of the major branches of government in the 2024 election, combined with the announced cabinet picks in the Trump 2.0 administration eliminate any guardrails to protect against the risk of more extreme tariff policies. While we agree that there are fewer guardrails than in the first term, there is reason to believe that important checks and balances still exist.

- First, the Republican House and Senate Majorities are slim. In the House, there is currently a majority of only 6 seats (with 1 seat still undecided in California’s 13th district), so, in theory, it would only take 3-4 reluctant Republicans to flip the House majority on a particularly contentious issue. The House mid-term election cycle typically begins only about 12 months after the January inauguration, so Congress will be highly sensitive to any voter backlash. Even in the Senate (with a 53/47 Republican majority), we have seen the Republican leadership show a willingness to push back on some of Trump’s more controversial cabinet picks (e.g., Matt Gaetz).

- Second, inflation is a key factor. Republicans are fully aware that a large part of the downfall of the Democrats in 2024 was voter frustration with cost-of-living increases. Even though the rate of inflation had already declined sharply in the last year of the Biden term, overall price levels remained highly elevated compared to 2021. The distinction between inflation rates and price levels is important in the context of trade tariffs. Goldman Sachs has suggested that the tariffs could raise core consumer prices, which exclude food and energy, by as much as 0.9%. Other economists argue that the impact of tariffs on prices is a ‘one-off’ increase – boosting inflation in the first year they are imposed but having little or no inflationary impact in subsequent years. However, voters have long memories, with a tendency to anchor on what they perceive to be ‘fair’ price levels for key goods and services.

- Third, the S&P500 may prove to be a critical guardrail. Trump often proudly refers to equity market performance as his personal report card. So far, markets have rewarded his victory as the index has hit new highs. Also, some offset to disposable income reductions from tariffs may be provided by an extension of tax cuts. However, tax cuts tend to disproportionately favour higher-income groups with a lower propensity to spend. Lower-income groups with higher spending propensities tend to get hit harder by tariff increases, which ultimately depress aggregate consumption and overall economic growth. The North American supply chain is tightly integrated. According to the Economist magazine, nearly $1 trillion worth of goods crossed the northern and southern borders of the United States last year. Half of America’s fruit and vegetables come from its two neighbours. And more than half the pickup trucks sold by GM in the United States are made in Canada or Mexico, which is why the firm’s share prices fell by 9% on the day after Trump’s tariff announcement.

3. What are the likely outcomes and investment implications?

An optimistic scenario might also draw on history to find an analogy between the trade situation the US faces today with Chinese imports and the situation it faced with imports from Japanese and European carmakers in the 1980s. Although the Reagan administration did not impose heavy tariffs, it did initiate a pronounced weakening of the US dollar in 1985 which effectively raised prices of imports to US consumers. The 1985 Plaza Accord between the US, Japan, France, West Germany and the United Kingdom did exactly that. The US dollar index (DXY) depreciated by over 40%3 from the time of the agreement until it was replaced by the Louvre Accord in 1987 – effectively making import prices prohibitive to US consumers. Japanese and German carmakers invested heavily in building assembly plants in the US, creating jobs in the process. One can imagine a scenario where tariffs on China are used as a tool to incentivize Chinese companies to build and assemble more in the US, thereby creating a win/win outcome for all parties. Alternatively, heavy tariffs could be implemented more permanently to more fully decouple the US economy from China and other countries, including allies.

No one knows whether Trump sees tariffs as negotiating tools, or the degree to which he wants to shut down trade as an end goal. It might be tempting to assume that tariffs are simply a dramatic way to gain leverage. This seems to be the base case assumption in markets today. Trump has reinforced this view by stating that, following his recent tariff threat, he had a “wonderful conversation” with Claudia Sheinbaum, Mexico’s president. In 2019, he threatened levies of 25% on all Mexican goods, only to do nothing when Mexico and the United States reached a border deal.

From our perspective, the most likely outcome is that neither scenario will soon emerge as the definitive result. Yes, the imposition of some incremental tariffs on China are almost inevitable in the early days of the administration, but probably not to the extreme levels floated in the campaign (e.g., 60% to 100%) which would cripple US supply chains. The very fact that Trump referenced a 10% figure in late November gives one a sense of the likely starting point. In addition, tariffs on the rest of the world will likely be targeted at specific sectors, for example automotive. But in our view, it is highly unlikely Trump will ever take the threat of extreme tariffs off the table, nor will he revert to a low tariff regime.

More likely is that over the next four years, the tariff messaging from the Trump administration will continually alternate between pragmatism and ideology. In other words, unpredictability may be a strategy in itself.

Such a policy of strategic unpredictability will have specific investment implications:

- From an economic perspective, the cost of uncertainty is high. According to the IMF, more than half of the damage to global growth from tariffs will stem from firms deciding to sit on their hands while they ascertain the fallout from the trade war. In a c. 10% global tariff scenario4, the IMF forecasts a -0.6% cumulative hit to global GDP over the next 2 years, including uncertainty effects. In a scenario where Trump follows through with his 25% tariff threat on Canada and Mexico, combined with an additional 10% on China, J.P. Morgan estimates a -0.7% hit to US GDP.

- From a regional perspective, Europe will likely bear the brunt of the uncertainty around tariff threats, and hence suffer the largest economic drag, estimated at -0.7% cumulative over the next two years by the IMF.

- Inflation would likely rise modestly (by an incremental +0.2% in the US) on tariffs according to the IMF, but the reduced economic activity from uncertainty would offset most of that. In the specific Canada/Mexico/China tariff scenario referenced above, J.P. Morgan sees a +1.0% increase in US inflation. As noted earlier, Goldman Sachs has suggested that the tariffs could raise core consumer prices, which exclude food and energy, by as much as +0.9%. Again, a tariff-induced inflation rise would likely be seen as a one-off price level increase rather than a structural increase in the inflation rate.

- Interest rates: Even if temporary, higher tariff-induced inflation could force the Fed to curtail the pace of rate cuts and perhaps even raise rates. Although a scenario analysis conducted by the Fed in September 2018 implied that it should look through the impact of tariffs on prices, this only would apply if inflation expectations remain well anchored. Having been badly burned by the “transitory” narrative three years ago, the Fed might be reluctant to label the inflationary consequences of tariffs as transitory again.

- Currencies: The combination of higher interest rates and reduced demand for imports would likely push up the value of the US dollar against its trading partners.

- Equities: US manufacturing companies rely heavily on global supply chains. Tariffs would increase input costs. In addition, a stronger dollar will limit exports and reduce the dollar value of overseas revenues. According to BCA, a standard rule of thumb is that every 1% appreciation in the trade-weighted dollar lowers S&P 500 EPS by 0.25%. The trade-weighted dollar has strengthened by 1.9% since the election and 4.8% since late September. There would also be greater geographic divergences, with China and Europe likely further underperforming the US.

- For portfolios, strategic uncertainty above all implies elevated volatility and dispersion. Portfolios should be constructed with exposure to multiple asset classes and geographies. Active managers in general, and Absolute Return managers in particular, will benefit from wider dispersion opportunities.

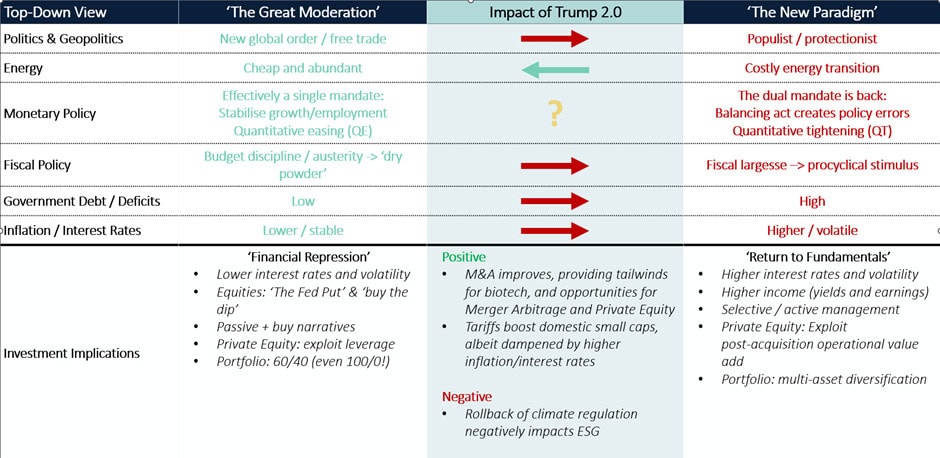

To conclude, we believe tariffs and other Trump 2.0 policies are broadly consistent with our “Back to Fundamentals” Paradigm Shift detailed in our Insights publications of the past two years. If anything, these policies serve to turbocharge many of the shifts detailed in Exhibit 1 below.

Exhibit 1: Trump 2.0 policies accelerate the shift to “The New Paradigm”

Source: Partners Capital Analysis

As always, we welcome your thoughts and feedback on the above. We will continue to monitor developments and keep you updated as our thinking evolves.

Footnotes

- World Bank WITS database

- Source: US International Trade Commission

- Source: Bloomberg

- IMF 2024 WEO: Tariff scenario assumes trade tensions lead to a permanent increase in tariffs starting in mid-2025 and affecting a sizable swath of global trade. The United States, Euro area, and China impose a 10% tariff on trade flows among the three regions; a 10% tariff is also levied on trade flows (in both directions) between the United States and the rest of the world. The increase in tariffs directly affects about one-quarter of all goods trade, representing close to 6% of global GDP.