Whitepaper

Recession Playbook

3 February 2019

Our Recession Playbook is our strategy for managing your portfolio through the coming few years in the face of a potential global recession. Given that almost all past bear markets have coincided with global recessions, we make little distinction between a strategy for investing through recessions or protracted market downturns. We see them as one in the same. While our work is ongoing, our playbook includes two key elements:

1. Reallocation of market exposures (or beta) in favour of those whose valuations have moved ahead or behind what is implied by fundamentals. Our aim is to measure over- or under-reactions across asset classes (and sub-asset classes) so that we can discern what is mispriced relative to a probabilistic range of outcomes. These assessments are made based on our in-house research, conversations with our asset managers, and inputs from trusted experts. This requires constant monitoring of market valuations and nimble tactical asset allocation to capitalise on these opportunities.

2. Reallocation of sources of excess return (or alpha) towards those strategies which are expected to perform well through the various stages of the business cycle, especially through a recession. Ideally, these sources of alpha would be uncorrelated, or even negatively correlated with market returns. Given that most active managers experience a higher correlation between alpha and beta in a stressed market environment, we are focused on maintaining balanced portfolios with strategies which are more likely to outperform in a market correction. These strategies are typically found within absolute return and alternative alternatives.

Our Recession Playbook analysis starts with a framework for how economic cycles work. We then look at how different asset classes (and sub-asset classes) have historically performed in recessions, before turning to a more detailed understanding of different types of recessions. Armed with a view of the three most likely recession scenarios, we then look across asset classes (and sub-asset classes) to understand how each might perform. Finally, we summarize a list of potential actions that clients should consider as the central levers of the recession playbook.

Most investors who anticipate a recession are focused on timing market risk (risk on vs. risk off) or timing the mix of market exposures. In contrast, we are looking to identify where we are in the cycle focusing on the consensus of investors. We believe that the outlook for investment returns will generally be more attractive when investors are depressed and fearful – resulting in falling asset prices, and unattractive when they are greedy and euphoric – resulting in rising asset prices. Today, we are somewhere in-between these two extremes, with no signs of either fear or euphoria, suggesting that we should not be incurring an opportunity cost by being overly cautious. Accordingly, our portfolios are today positioned neither defensively nor aggressively, though we are preparing ourselves as the natural outcome of market corrections is that there are typically more attractive investment opportunities.

During the onset of a recession, investors need to remain vigilant in monitoring the market landscape for opportunities to pick up high-quality assets at discounted prices. These are difficult environments, but they also coincide with the best opportunities. In the midst of a recession, the worst performing assets are highly leveraged, cyclical and speculative. Bankruptcies and defaults (or the fear of bankruptcies and defaults) are the catalysts for a deep opportunity set for distressed investing.

Reallocation of market exposures (beta)

Howard Marks summarised the opportunity for distressed investing in his recently published book, Mastering the Market Cycle.

Highly leveraged companies have huge debt loads on their balance sheets. Interest payments remain constant while the recession brings a decrease in revenue, increasing the risk of bankruptcy. Cyclical stocks are tied to employment and consumer confidence, which are battered in a recession. Speculative stocks are richly valued based on optimism among the shareholder base. This optimism is tested during recessions, and these assets are typically the worst performers in a recession.

On the other hand, counter-cyclical stocks do well during recessions. This group is composed of companies with dividends and massive balance sheets or steady business models that are relatively recession-proof. Some examples of these types of companies include utilities, consumer staples and defense stocks. In anticipation of weakening economic conditions, investors tend to add exposure to these groups in their portfolios.

Once the economy is moving from recession to recovery, investors should adjust their strategies. This environment is marked by low interest rates and rising growth. The best performers are those highly leveraged, cyclical and speculative companies that survived the recession. As economic conditions normalize, they are the first to bounce back. Counter-cyclical stocks tend not to do well in this environment; instead, they encounter selling pressure as investors move into more growth-oriented assets.

This is the theory. The practice is very different. All of what Howard refers to requires insights about where we are in the cycle that differ from the consensus, and requires us to understand how an impending recession will differ from those in the past. For example, as we start 2019 the most expensive sectors are already the counter-cyclical sectors of consumer staples and utilities with forward PE ratios that are +0.5 and +1.4 standard deviations above their respective 30-year averages, even though experts believe that we are two years away from recession. Large pools of distressed capital have been raised and ready to pounce for years. But with little to do, impatient investors have bid up any opportunity with the slightest whiff of distress to levels which offer unattractive returns.

Therefore, any recession playbook requires an extremely tactical approach, whereby valuations are constantly monitored for mispricing and opportunities to go over/underweight. Our recession playbook explicitly focuses on asset classes (and sub-asset classes) which have historically performed well in and around recessions.

A crucial observation regarding asset classes that are expected to outperform through a recession or market correction is that such investments typically have an opportunity cost over the long run as they tend to underperform their counterparts in normal or rising market environments. Therefore, outperforming in a recession can only occur as a result of successfully timing entry into such assets in anticipation of a recession-based market correction.

The upcoming recession will not be like any other recession in the recent past. The recession caused by the Global Financial Crisis was driven by excesses in the financial system, most of which do not exist today. The recession caused by the technology bubble and subsequent bust in 2000-01 was driven by over-exuberance in just one sector which ultimately brought down the rest of the global economy. The next recession could take on many forms with many different drivers. The most likely causes for the next recession will be around geopolitics, trade wars, monetary policy mistakes and fiscal policy mistakes. Any specific playbook moves must take full account of the factors that are most likely to drive us into recession.

Reallocation of sources of excess return (alpha)

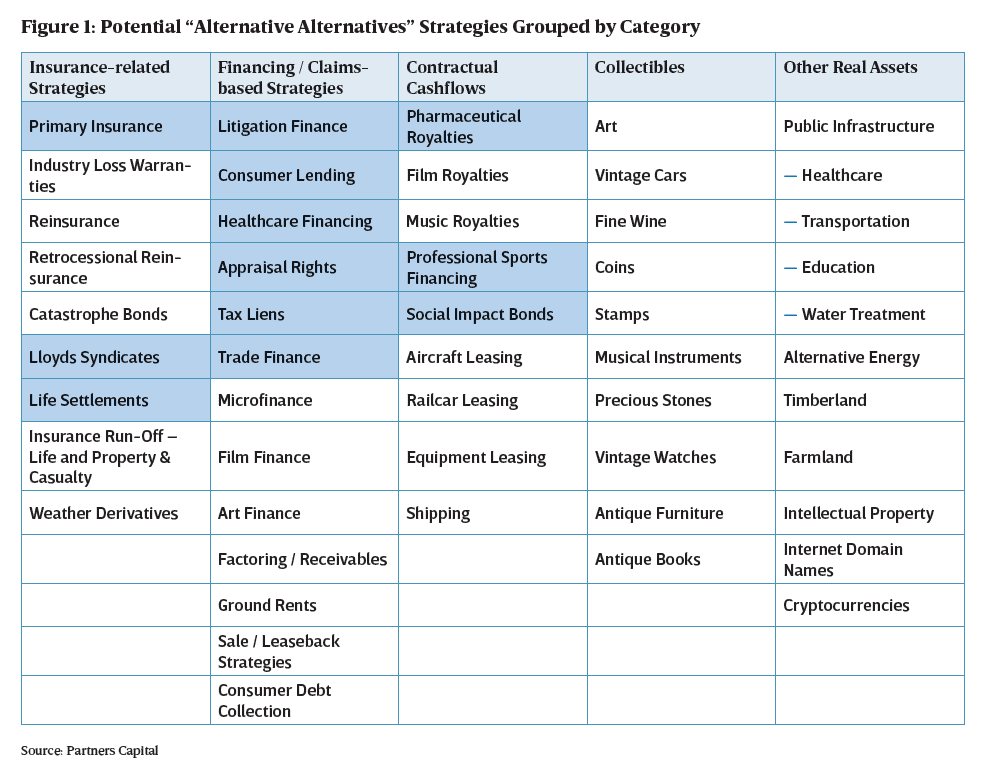

The ultimate recession-proof strategy is one which generates returns that are completely uncorrelated with the business cycle or with financial market returns. There are two categories of uncorrelated return streams:

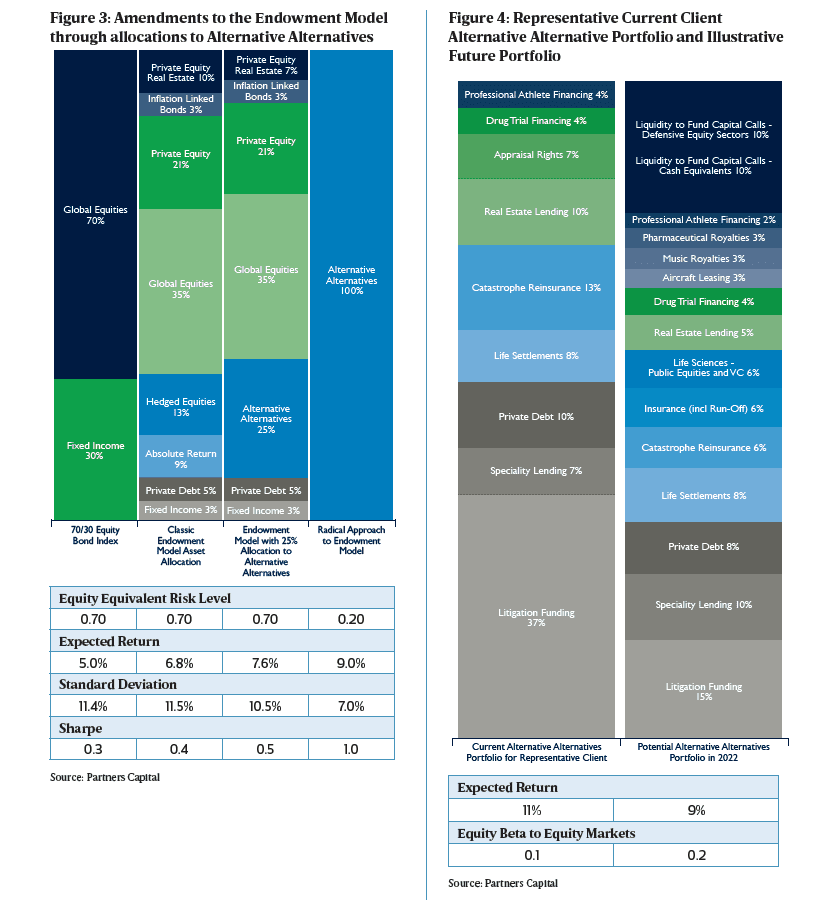

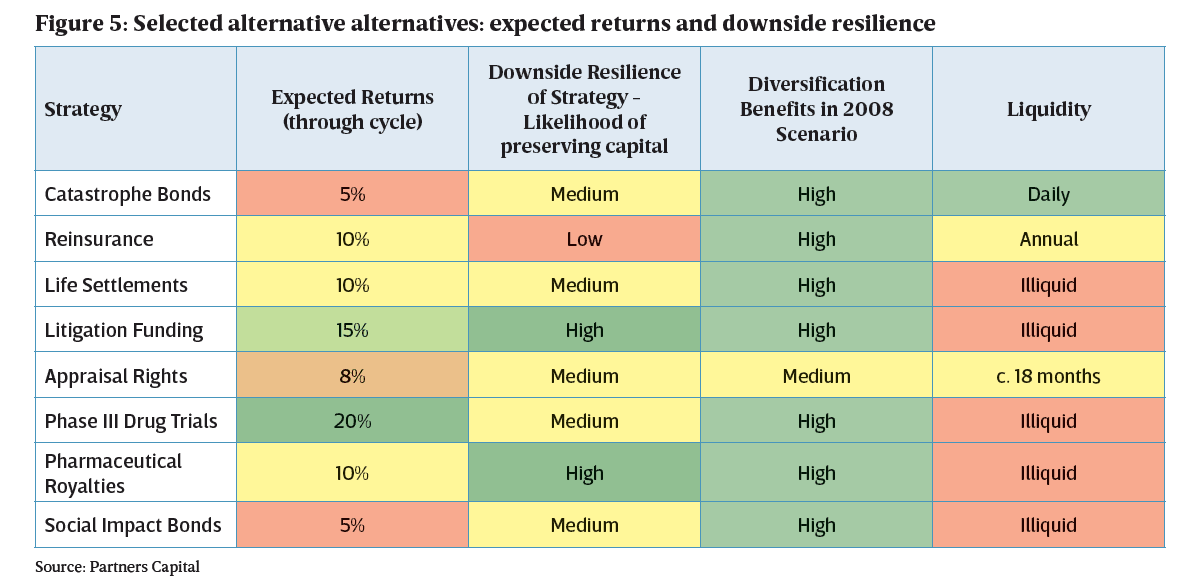

1. Alternative alternatives – these are asset classes that derive their risk premiums from non-financial market risks such as insurance, life settlements, litigation finance, royalties, etc. For the past five years, we have been building diversified portfolios of such uncorrelated investment strategies which have limited or no market timing requirement. While these strategies are not without significant risks, they are risks which are orthogonal or uncorrelated to market risks – what some might call the “holy grail” of investing. An increased allocation to such strategies is the central pillar of our recession playbook.

2. Absolute return strategies – these are active strategies which are expected to either excel, or at least not be negatively impacted, in an economic recession or market correction. Historically, we have seen outperformance in market downturns in strategies such as macro, trend-following, and equity market neutral hedge funds strategies. We also see specific “long-volatility” portfolio overlay strategies such as Capula or Niederhoffer performing well in periods of markets downturns, but these come with a performance drag if markets continue to grind higher. Certain active strategies tend to be more challenged in periods of market downturns including hedged equities and hedged credit strategies, both of which exhibit higher stress beta when markets

fall sharply.

1. How Economic Cycles Work

We would have no recessions or cycles if it were not for excesses in one form or other. Economic cycles are fluctuations between periods of expansion and recession which are caused by excesses. Excesses come in many forms but most commonly when supply of goods and services is out of kilter with demand for those goods and services. If demand always stayed perfectly in line with supply, economies would grow steadily in line with the growth of the working population and productivity improvements.

When demand exceeds supply, we see inflation and rising interest rates start to curb consumer spending and business investment, causing defaults and a decline in growth. When supply exceeds demand, we have the opposite – low prices, low interest rates, high investment and consumption driving growth above normative levels. Excesses can also come in the form of borrowing and lending or in the form of investor exuberance for certain assets creating asset bubbles (e.g., 1999 technology bubble) that burst and cause a decline in economic activity.

The four generalised stages of an economic cycle are: 1) expansion, 2) peak, 3) contraction and 4) trough. We do not believe that we can predict exactly when cycles turn and recessions occur, but knowing where we are in the cycle gives us a view on the range of likely outcomes and should enable us to know when to be defensive or aggressive in our investment strategy. Figure 1 makes the point.

We reached the bottom of the current economic cycle in 2009 (Figure 2), during the depth of the global financial crisis, which led to accommodative monetary and fiscal policies across most economies. Low interest rates induced credit growth, which helped to drive the recovery and expansion of the current cycle that has gone on for the past 10 years and counting. If the US recovery persists beyond July 2019 it will be the longest uninterrupted US expansion since 1785. Global economic growth remains strong, but there is now limited slack (difference between actual and potential growth) in the economy given the high capacity utilisation and low unemployment rate. This is a sign that we are at the late expansion phase of the cycle.

It is easier to identify where we are in the cycle but much more difficult to gauge how long the current cycle will last. The closing of the output gap is the economists’ primary indicator of the peak of the economic cycle, but the time between peak (proxied by closure of output gap) and a subsequent recession is not terribly predictable, having varied from one to six years in recent cycles. (Figure 3 overleaf. So “knowing where you are in the cycle” may not be as helpful as Howard Marks suggests.

Given the above, predicting when the cycle will turn is a futile exercise. Instead, we believe we are better off starting with what we can be more confident of – which is that we are in the late expansion phase – and position our portfolios accordingly, whether aggressively or defensively. We quote Howard Marks again from his book Mastering the Market Cycle and what he has learned from past recessions:

“There are two things I would never say when referring to the market: “get out” and “it’s time.” I’m not that smart, and I’m never that sure. The media like to hear people say “get in” or “get out,” but most of the time the correct action is somewhere in between. Investing is not black or white, in or out, risky or safe. The key word is “calibrate.” The amount you have invested, your allocation of capital among the various possibilities, and the riskiness of the things you own all should be calibrated along a continuum that runs from aggressive to defensive.”

“…when the upcycle has gone on for a long time, when valuations are high, when optimism is rampant, when everybody thinks everything’s going to get better forever, when the economy has been moving ahead for 10 years and it looks like it’s never going to stop, then usually, the enthusiasm has carried the prices to

such a high level that the odds are against you. Just knowing that is a huge advantage in investing. You should know that when we’re low in the upcycle, that’s a time to be aggressive, put a lot of money to work, and buy more aggressive things, and when the cycle has gone on for a long time and we’re elevated, that’s the time to take some money off the table and behave more cautiously.”

“Oaktree’s mantra recently has been, and continues to be, “move forward, but with caution.” The outlook is not so bad, and asset prices are not so high, that one should be in cash or near-cash. The penalty in terms of likely opportunity cost is just too great to justify being out of the markets.”

However, it should be noted that we do not blindly follow the above-mentioned view to be defensive in the late cycle. What is perhaps more important to consider is an understanding of the degree to which current valuations accurately reflect the likely outcome in the future. There might be instances where we may be positioned more aggressively in this late expansion stage because the market has priced in an overly pessimistic outcome. In order to understand these dynamics, valuation will play an important role in our decision-making.

2. Performance in Past Recessions

Below we look at the empirical facts around how various assets have performed through recessions breaking those assets into three categories: asset classes, equities sectors and excess returns/alpha sources.

Performance of asset classes in recessions

Investment grade (IG) bond spreads have historically been a better predictor of a recession than equity markets. IG spreads typically rise to 280 bps or more in a recession, and average 160 bps when not in a recession. Therefore, if IG spreads rise to 220 bps, halfway between these two levels, we can crudely infer that the market is pricing a 50% probability of recession. In this way, we can determine the market’s perception of risk and evaluate it against the fundamentals. This approach produces similar results to the Federal Reserve’s smoothed model of economic recessions.

In both the lead up to a recession and during a recession, government bonds, inflation linked bonds, investment grade bonds and gold have provided the best protection. It must be noted that ahead of every past crisis, 10-year US Treasury yields were significantly higher than the 2.7% yield offered in January 2019. For example, the 10-year yield was 4.5% ahead of the Global Financial Crisis, 6.4% ahead of the dot-com bubble and 8.3% ahead of the 1990s oil shock.

Figure 4 shows the performance of different asset classes during previous recessions and bear markets. Unsurprisingly, global developed market equities experienced the worst performances, averaging -25.6% from the events. Traditional safe-havens such as US Treasuries, Japanese Yen and the Swiss Francs have tended to perform strongly, averaging returns between 7-10%.

The key learning from this analysis is that, at an asset class level, what has worked in the past may not work in the future as starting bond levels are at historical lows, and the government is already fiscally extended. Additionally, rotation within asset classes may help, but careful consideration needs to be given to the relative pricing and valuation of each sector as we will now discuss below.

Performance of equities sectors in recessions

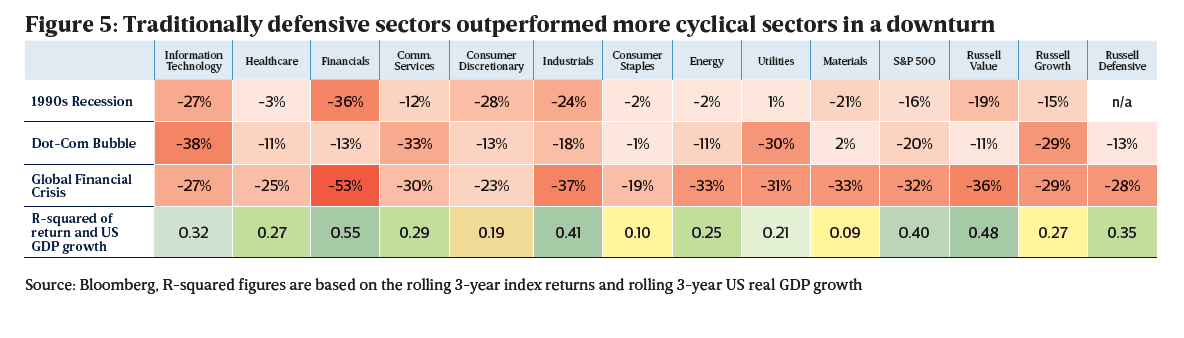

Figure 5 focuses on the sector level performances of US equities (S&P 500 index) during the last three recessions. Consistent with widely held views, traditionally defensive sectors (consumer staples, healthcare) lost less than more cyclical sectors (financial, industrials and technology). With drawdowns of -30% and -31% during the past two crises, it does not appear that the utilities sector has actually delivered any defensiveness.

Analysis of sector performance over the last 3 recessions shows that once the market starts to price in a 25% probability of a recession, defensive sectors such as utilities and consumer staples tend to significantly outperform the market. For example, in the Global Financial Crisis, during the period between the increased recession fears (August 2007, as determined by the sharp rise in IG bond spreads that month) and the actual onset of the recession (December 2007) utilities and consumer staples rallied +10.3% and +7.2% while financials and consumer discretionary declined -13.3% and -11.4% respectively. It is similar for the dot com bubble, where between the increased recession fears (Feb 1997) and the actual onset of the recession (Feb 2000), utilities and consumer staples had an annualised return of +32.4% and +20.9% respectively, while technology, communication services and consumer discretionary had annualised declines of -55.4%, -30.6% and -7.7% respectively. The result was that when the actual recession hit, valuations in some of the defensive sectors such as utilities were so stretched that these sectors suffered declines on a par or worse than the broader market as panic selling caused investors to flee.

Consideration must also be given to the expected policy response in a recession, and the impact this will have on asset prices and equity sectors. The traditional policy response has been a swift reduction in interest rates by the central banks, which has been beneficial to bonds and bond proxies such as utilities. In the Global Financial Crisis, the US Fed cut the policy rate from 5% to 0%. During the dot-com recession, the rate was cut from 5.9% to 1.8%, and in 1990 the policy rate was cut from 8.1% to 3.5%. In each case, the cut in policy rate required to reboot the growth cycle was more than 4.5%. As of February 2019, the effective Federal Funds rate is 2.4% in the US. This likely means that if policy makers maintain the “zero-bound” on interest rates, they will need to pursue alternative strategies in addition to rate cuts to sufficiently stimulate growth.

Quantitative easing is one such approach, but the Fed’s own analysis suggests that the cumulative impact of QE post 2007 was a reduction in yields of 100 basis points (Bonis, Ihrig, Wei, April 2017). This is despite the Fed’s balance sheet ballooning from $900 billion in 2008 to a peak of $4.5 trillion in 2017. If more stimulus beyond rate cuts and QE is required, it will likely need to come from government spending in a similar form to that of Roosevelt’s “New Deal” in the 1935. Such policies focused on injecting capital into the real economy will likely be more beneficial for sectors such as industrials, materials and infrastructure, and less beneficial for bonds and bond proxies than previous policy responses have been. Here too there are limits, with government debt already at peace-time highs and expected to worsen over the next five years.

Performance of alpha in recessions

We define alpha as those returns in excess of traditional market exposure-based returns (or betas). These generally fall into one of two buckets.

Firstly, these include alternative alternatives that derive their risk premiums from non-financial market related risks such as insurance, litigation finance, royalties, etc.

Secondly, these include certain absolute return strategies that derive their risk premium from manager skill rather than directional market bets. These have historically included strategies such as macro, trend-following, and equity market neutral hedge funds strategies.

An increased allocation to such strategies is the central pillar in any sound recession playbook. Timing allocations to these strategies depends on the relative attractiveness vs government bonds, gold and other traditional safety net allocations. When bond yields are extremely low as they have been in recent years, the opportunity cost of holding bonds is high. This is where absolute return strategies may be preferred. We should highlight that in extreme market or economic shocks, government bonds and gold will outperform absolute return strategies. But in a more typical recession, after any shock, the returns on the alternative asset strategies may be higher than government bonds and gold.

Theoretically, a strategy that is totally uncorrelated to economic growth should be able to produce the same expected return throughout the cycle. This is not to say these strategies do not have risk, only that the risks are uncorrelated. An example of such a strategy is litigation financing, whereby a manager provides the financing and legal expertise to fund litigation and receives a portion of the settlement or award if successful. Track records of experienced litigation funders demonstrate that the strategy exhibited virtually no correlation to the 2008 recession. Furthermore, the strategy may even be considered counter-cyclical, since a recession leads to more insolvencies (a source of potential demand for litigation funding) and a greater propensity for claimants to litigate with third party funding.

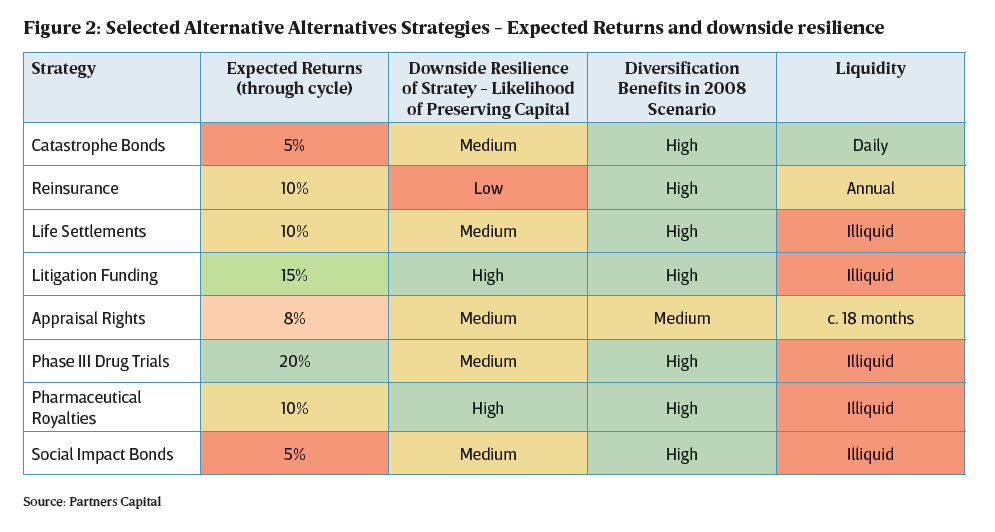

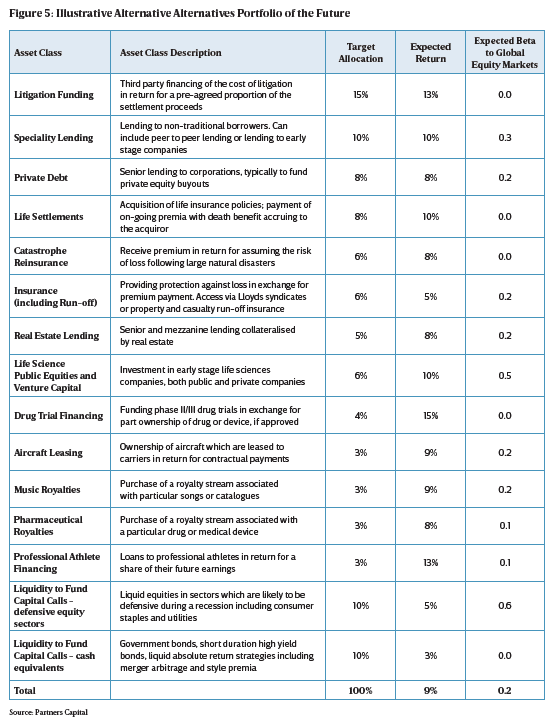

Figure 5 below is our assessment of the expected return provided by various alternative alternative strategies throughout the cycle, and their relative downside resilience in an economic slowdown. In the fourth column, you can see that virtually all of these strategies offer significant diversification in a 2008 scenario.

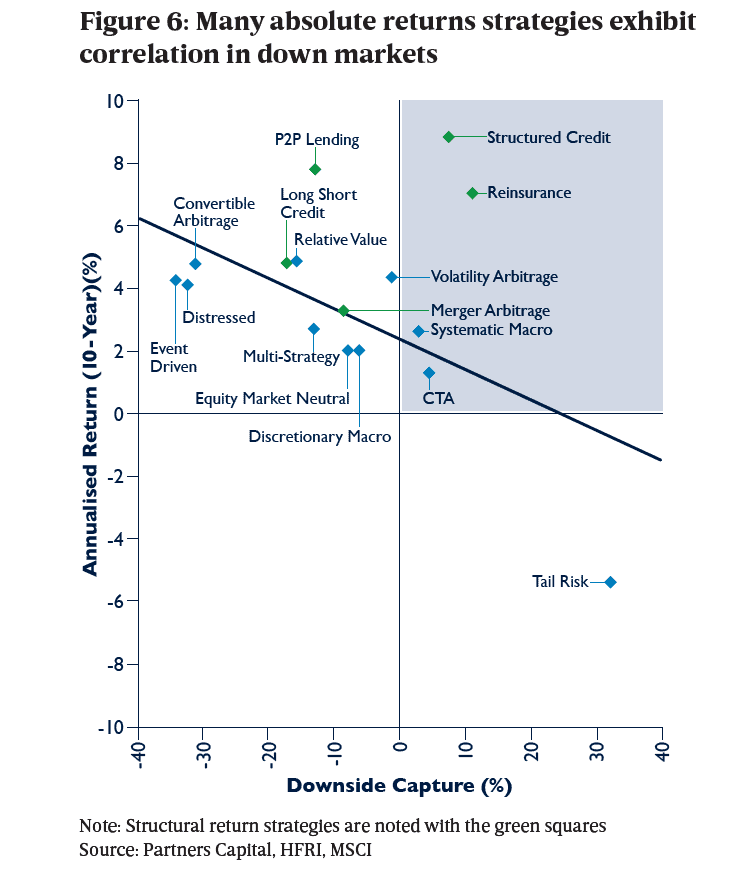

Absolute return hedge fund allocations have two purposes in our portfolios: 1) to provide an attractive total return with little correlation to market risk, and 2) to preserve capital in a large market correction, acting as a supplement to (or substitute for) classic safety net assets. These objectives, however, are in conflict with one another as higher expected returns are generally achieved by taking greater market risk. As seen in Figure 6, most absolute return strategies with higher return profiles generally have higher downside capture. Downside capture reflects the relative drawdown of the strategy in an equity market decline – for example, the ~10% downside capture for merger arbitrage means a -1% decline for the strategy in a -10% equity market decline. While structural return strategies have generally delivered higher returns with greater consistency than skill-based strategies, they can also be susceptible to large “left-tail” risks, as happened to Reinsurance strategies in 2018.

3. There is no such thing as an “ordinary” recession

This recession playbook must contemplate not what has done well in past recessions, but rather what will work well in the range of likely recessions going forward. The classic narrative on the causes of a recession is as follows: a buildup of excess credit leads to rising and eventually exuberant spending and investment, resulting in an overheated economy, rising wages and inflation. The Central Bank steps in to cool down the economy but instead drives the economy into recession.

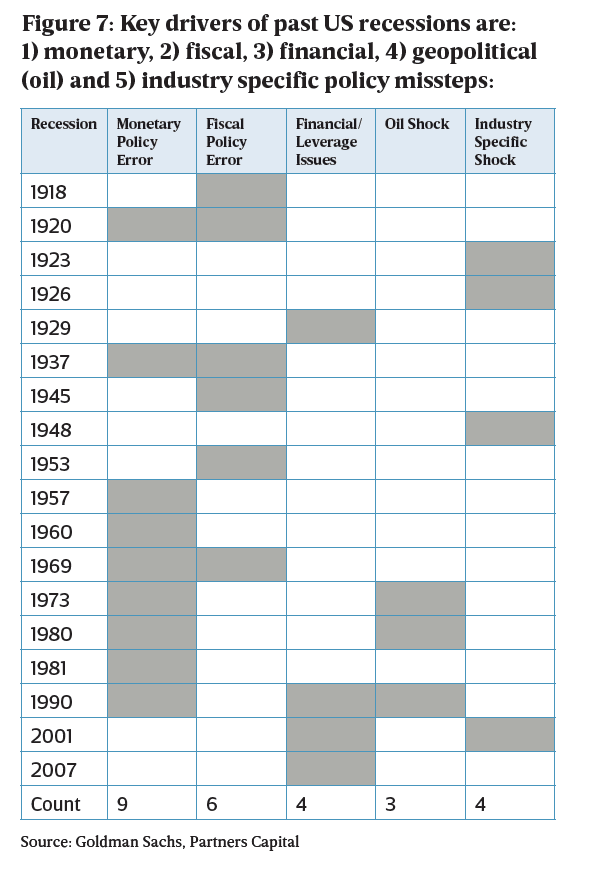

If this narrative is true, then Figure 7 would only point to monetary policy as the sole driver of recession. While monetary policy has played a role in seven out of the last nine US recessions, Exhibit 21 also shows that: 1) fiscal tightening, 2) financial imbalances, 3) oil shocks and 4) industry specific imbalances have also been to blame for many of the past recessions.

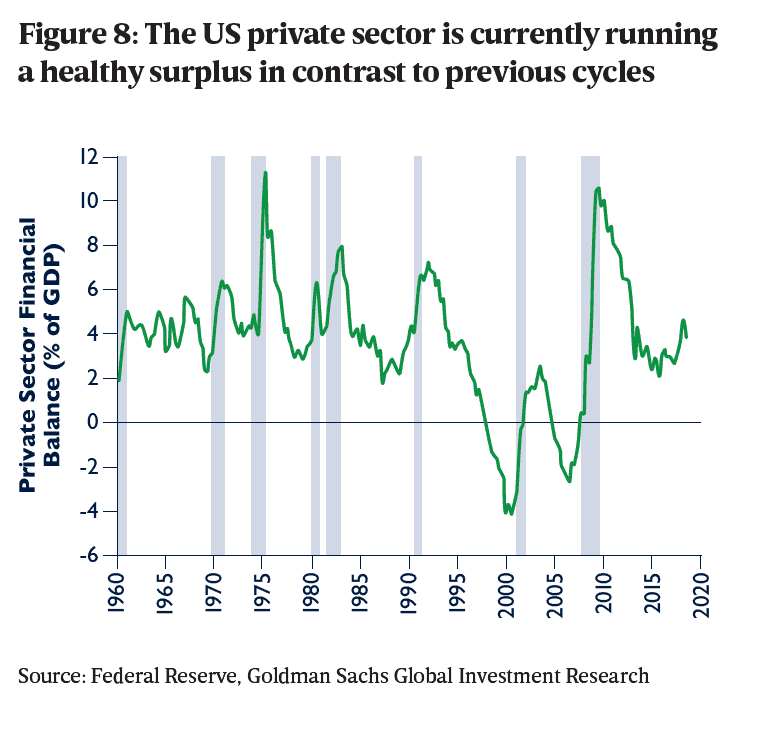

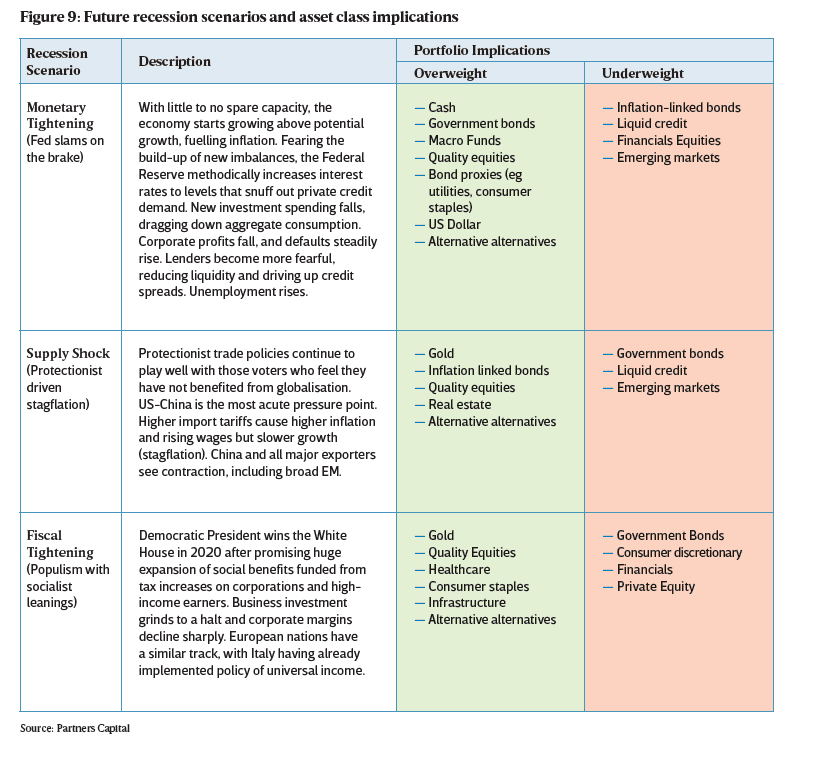

Having concluded that industrial, oil and financial risks are less likely to cause the next recession, we next review what might end the current expansion. We see three plausible paths to a recession in the medium-term:

1. An economic overheating as actual growth exceeds potential growth, ultimately causing the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates by too much, quashing private investment and tipping the global economy into a recession.

2. A supply shock caused by renewed trade war and protectionist policies that cause global growth to slow and inflation to rise, leaving everyone worse off.

3. A fiscal tightening caused by a populist driven political change that promises to redress rising inequality by implementing significantly higher taxes on corporations and wealthy individuals, leading to a sharp decline in private investment spending and a fall in growth.

Each of these is only likely to cause a recession several years out into the future and even then may not have sufficient impact to cause recession. But the differing paths imply different return outlooks for different asset classes from this point on. Additionally, these scenarios are not necessarily mutually exclusive and some combination may cause the next recession, but we review them on a discrete basis to hone in on the investment implications of each. Figure 9 provides some explanation of each scenario and identifies which assets we think will perform best.

4. Expected Asset Class Performance in a Recession

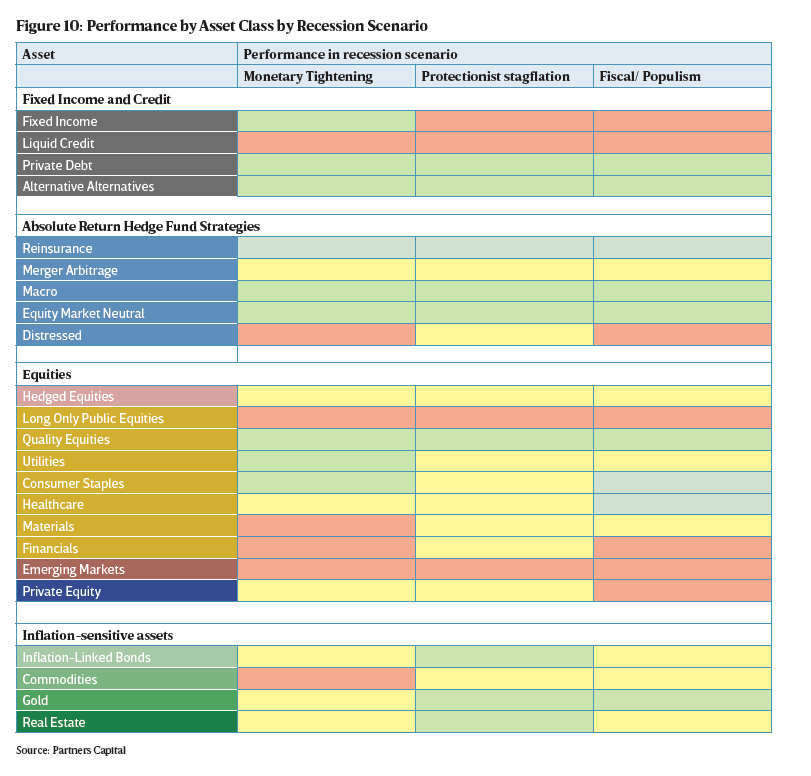

The combination of historical performance in a recession, current valuations and the expected cause of future recessions are the key inputs to our recession playbook. In Figure 10 we summarise with our green, yellow and red color coding, the relative attractiveness of each asset class in each of the three types of recessions above, with green being defensive, neutral or attractive in each recession scenario.

Looking at fixed income and credit-related asset classes, private debt and alternative alternatives offer the best opportunities in the face of recession. The classic hedge, government bonds, are likely to suffer in the coming recession due to the high likelihood of rising rates and inflation, but the flight-to-safety effect will dominate when the crisis hits its peak. Timing is critical, however, as the bulk of the value accretion often happens in a matter of days in shock-based recessions. Our recommendation is to wait for rising rates (e.g., US 10-year Treasury yields hitting 3.5% vs 2.7% today) before adding significantly to interest rate duration.

Alternative alternatives like litigation finance, insurance and life settlements are expected to perform no differently through a recession. Accordingly, they are core to our recession playbook and warrant 10% allocations across client portfolios where illiquidity budgets allow.

Turning to absolute return hedge funds, a diversified portfolio of these strategies should continue performing through a recession so long as any credit or equity beta can be appropriately neutralised. However, many absolute return strategies will be susceptible to stress beta or higher alpha correlation in a market downturn, and thus balanced and defensive portfolio construction and manager selection is critical.

As you would expect, finding a place to hide from the effects of recession is nigh impossible in anything related to global equities as you can see below. Consumer staples and healthcare are two sectors which are likely to defend the best among public companies. Anything in the biotech and broader life sciences fields should do relatively well through the recession, despite the volatility around public and private pricing of such assets. Private equity commitments made today generally are committed during and beyond the life of a recession enabling disciplined PE investors to sit on their hands until they see attractive opportunities. Holdings going into the recession are operationally and financially challenged, but with the right PE sponsor backing, their management teams can usually lean into the opportunities, while their public counterparts are retrenching.

Looking below at real estate and other inflation-sensitive assets, only gold stands out as the obvious play. Inflation-linked bonds may benefit in inflation-driven recessions (protectionist trade wars), but the duration will get hit in the event of rising rates. Commodities demand dries up and prices fall unless it is more of a trade war related recession and protectionism drives higher domestic commodities prices. Property suffers a combination of operating and financial stresses, similar to leveraged buyouts, but with the benefit of tangible asset underpinning. This is generally a dry-powder distressed play.

5. Key levers of the Recession Playbook

While the previous section outlines our thinking at a granular asset class level, below we summarise the five broad levers that investors could use to enhance portfolio returns through a recession. The objectives are to position the portfolio more defensively, tap into more uncorrelated asset classes and take advantage of market dislocations to snap up bargains when opportunities arise. The nature and severity of a recession coupled with the investor’s liquidity requirements will dictate which levers are most suitable to any given investor.

1. Increase portfolio duration. Government bonds are the traditional safety asset. With yields on the US 10-year government bonds below 3%, close to historic lows, the potential gains accruing to bonds in the classic flight-to-safety is likely to be lower than in past recessions. However, the contractual nature of the coupon payments will help protect portfolio value in a recession. We recommend adding to duration when yields offer greater protection (e.g.,3.5% for US 10-year Treasuries vs 2.7% at present)

2. Increase allocation to “alternative alternatives” and absolute return hedge fund strategies. The

central focus of a recession playbook is seeking ‘off the beaten path’ return streams that are tied to unique risks that are not related to financial markets. The return drivers of these strategies are typically structural and quantifiable, and include litigation risk, insurance risk or human longevity risk, rather than a pure reliance on manager skill. By definition these return streams should have lower correlation to global growth and provide solid returns throughout the cycle.

3. Shift equity exposures to those sectors and subsectors with lower correlation to economic growth

a. Substantial overweight to hedged equities instead of long equities. Our preference for hedged equities stems from our belief that outperformance is easier to come by than for long-only managers, in part because they are typically more actively trading around positions and taking advantage of short-term volatility than long-only managers who have more of a “buy and hold” mentality. We believe that our hedged equities allocation can deliver an expected total return similar to long-only equities but with a significantly reduced level of market risk. We currently have a +5% overweight to hedged equities within our policy portfolio.

b. Within hedged equities, focus on specialist strategies in sectors with reduced fundamental sensitivity to economic cycles. We believe that growth in life sciences and biotech markets are ultimately driven by innovation in the development of therapeutics and growth in health needs of the global population, both of which should be minimally impacted by the economic cycle. We therefore expect that, while biotech markets may experience sharp mark-to-market moves as economic conditions change, they should outperform broader equity markets over a recessionary cycle. We also believe that the pervasive disruption benefiting technology companies should continue through a recessionary cycle, providing downside protection relative to broader markets for those technology companies trading at reasonable valuations and implied growth rates. Our specialist investments in more cyclical sectors are limited and are generally with managers with low net exposure.

Within long-only equities, our recession playbook has the following biases.

c. Overweight quality equities. Quality equities are marked by strong pricing power, durable competitive advantage, structurally higher margins and low leverage, all of which should cushion company fundamentals in a recession. In the past, quality equities have tended to defend well in a bear market. We note, however, that quality equities have performed strongly in recent years and are priced at relatively high multiples, reflecting market recognition of their attractiveness in the current environment and potentially reducing their defensiveness in a bear market.

d. Overweight healthcare, life sciences and technology service companies. Traditional defensive industry sectors such as utilities, healthcare, energy and consumer staples have historically fared better through recessions and bear markets. We note a number of caveats, however, that we believe make a wholesale rotation into these sectors unwise. Utilities is a very narrow market that has been upended by shifts in energy generation and transmission and where companies can see dramatic declines if forced to cut dividends for reinvestment or as a result of regulatory change. Energy has substantial swathes of exposure to the commodity cycle in oil and natural gas driven by global demand. Consumer staples continue to contain strong and enduring franchises but as a whole have experienced significant disruption in consumer behaviour. We are more constructive on healthcare, particularly life sciences, and we believe there is a group of technology services companies with recurring revenue business models and reasonable valuations that should also be defensive.

e. Underweight EM ex-Asia. We believe emerging markets as a whole would be negatively impacted by a global recession, with the lower quality, export-oriented and commodity-driven markets outside of Asia disproportionately harmed. Our policy portfolio for 2019 has zero exposure to EM ex-Asia markets like Russia, Brazil and South Africa. Our modest +2% overweight to EM is focused exclusively on China, India and other Asian economies which can be more independently managed through the fiscal and monetary policies of their respective governments. But a worsening trade war will not be kind to Asian suppliers to China. So, depending on the nature of the recession, our recession playbook could see a sudden reversal of our China overweight.

f. Re-balancing around extreme market moves. As with recent “recession scares,” we will watch for situations where equity markets price in a recession probability that is at odds with our own assessment and consider modest 2-3% moves in long equities exposure. For example, if we feel markets are materially underestimating the probability of recession, we will shift small amounts of equity exposure into liquid, low risk investments in order to provide “dry powder” for allocation into severely dislocated assets that would likely become available in a market correction.

4. Add gold exposure. Gold has historically been one of the best performing assets in times of market turbulence. During the ten periods of the most acute market stress since 1970, gold produced a median return of 8%. In only one of those ten periods did gold lose money, and that was during the aggressive central bank rate hiking cycle of the 1980s when the Federal Funds rate was increased to 19%. However, the opportunity cost of holding gold in stable or growth periods can be considerable, so timing is of paramount importance and is far from easy.

5. Prepare for distressed opportunities via special situation managers. In preparation for the eventual recovery, investors should be seeking out those managers with a proven track record, deep restructuring capabilities, strong alignment and the discipline to wait for the right opportunities. These relationships will need to be formed ahead of any downturn to allow for swift capital deployment. It is essential to find a patient manager since over the last five years, we have seen significant pools of capital being raised to acquire assets which did not fit the description of buying high-quality assets at a discount.

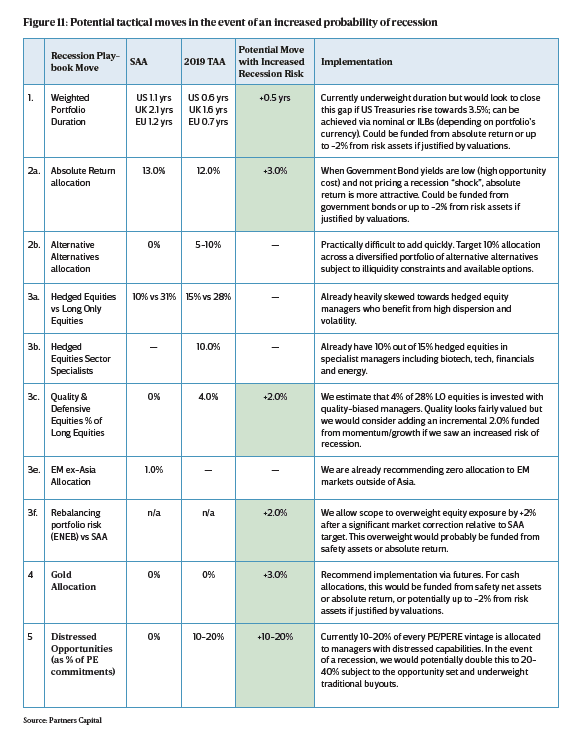

In Figure 11, we capture our Recession Playbook in a single chart, defining how far along we are in executing against each element of our playbook. In some client portfolios, we are already positioned well for recession on some dimensions like Alternative Alternatives. With other moves, like interest rate duration / government bond exposure, we are still waiting for valuations to move before executing that element of our playbook.

In conclusion, we do not expect a recession in the near-term, but we are mindful that asset class performance will be determined by the market’s perception of recession risks. Our tactical asset allocation for 2019 inherently reflects our current views of the probability of recession. However, if we were to see an increased probability of recession over the course of the year, we would consider implementation of some of the Recession Playbook moves outlined above which have not yet been put into place, subject to our views on valuations at that point in time and the evolution of the various recession scenarios.