Whitepaper

Making a Difference – Developing your Philanthropy Strategy

By Stan Miranda, Brendan Corcoran

14 July 2015

‘‘ Poor and restricted are our opportunities in this life; narrow our horizon; our best work most imperfect; but rich men should be thankful for one inestimable boon. They have it in their power during their lives to busy themselves in organizing benefactions from which the masses of their fellows will derive lasting advantage, and thus dignify their own lives. ” — Andrew Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth

Partners Capital enjoys the privilege of advising some of the brightest and most talented investors of our generation. Our clients have generated significant wealth by working their way to the top of the investment industry, starting and running businesses and investing their own money successfully. The wealth management industry refers to these individuals as “first generation” wealth creators. And virtually all of them grapple with a fundamental question: what is the purpose of wealth?

Every client of Partners Capital starts their relationship with us by completing a risk questionnaire. The first question in the questionnaire is:

What is the purpose of the assets that you are looking to us to manage (allocate percentage)?

- Living expenses for me and my family (__%)

- Start or invest in my current or future business (__%)

- Legacy for my children/grandchildren (__%)

- Philanthropic purposes (__%)

Answers vary hugely from one client to the next, with many of those with larger balance sheets having 50% or more of their wealth earmarked for philanthropy. Regardless of whether the allocation is 10% or 50%, most of our clients have yet to put in place a strategy for achieving that purpose. A significant number of our clients are shifting their priorities toward personal goals more related to “giving back” or making a difference in the world through the thoughtful deployment of their accumulated financial resources. We have had little to contribute in those discussions to date, so perhaps somewhat unusually, we chose to research a topic for this issue of our quarterly newsletter which has little to do with investing in the traditional sense. To that end, we have devoted several months’ of a small internal team’s effort to research the topic of “making a difference” to help our clients, friends and ourselves to achieve a meaningful philanthropic role for our capital.

As we get older and take stock of the financial resources we have been fortunate enough to earn and save beyond our own and our family’s needs, we realize the importance of deploying this capital in a way that means the most to each of us. We also realize that this can command a large personal investment of time.

Jack Ma of Alibaba voiced his recent realization:

“When you don’t have much money, you know how to spend it, but once you become a billionaire, you have a lot of responsibility; ….at this level, it is really not my money…The money I have today is a responsibility. It places the trust of people on me. I need to spend this money responsibly on behalf of the society.”

We have been hearing our clients voicing this realization more often recently, along with a frustration around how to find the purpose most meaningful to them and the most appropriate vehicle for achieving that purpose. Many clients are highly skeptical of the vast majority of charities, seeing them as poorly run, inefficient enterprises not worthy of deploying their donations. In this effort to help our clients in this area, we have looked for advisors, tools and frameworks and have not found any single place to direct them to kick-start the process. What we can offer, however, is a synthesis of the best learning from those who have been most thoughtful on the subject of “making a difference.”

We have found four particularly useful sources of insight on the topic of developing a philanthropic strategy:

- Andrew Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth”

- Tom Tierney’s Bridgespan Group, which is a nonprofit spin-off of strategy consulting firm, Bain & Company, set up to advise donors and charitable institutions to deliver exceptional social impact with their resources

- Sir Ronald Cohen, founder of Apax Partners, the global private equity and venture capital firm; today a pioneer of social impact investing

- Examples of what ten of today’s most thoughtful philanthropists are doing

To be clear, the question we are attempting to help you answer is “How do I go about establishing a clear purpose and strategy for making a difference through my philanthropic efforts and how do I get started down that path?”

Required Reading: The Gospel of Wealth

We encourage you to start this journey with Andrew Carnegie’s 1889 essay “Wealth” (better known as “The Gospel of Wealth”). Carnegie, the great American industrialist, reasoned that there are only three ways to distribute surplus wealth: 1) to create a family legacy; 2) to be left to charity at death; or 3) to be “administered for the common good” during the lives of the wealthy. As was the fashion of his generation, Carnegie believed it was the duty of wealthy men to avoid ostentatious spending and extravagance.

In blunt terms, Carnegie rejects the first and second alternatives, the family legacy and charitable giving at death. Family legacies ruin the children, he argues, pointing to the stagnancy of the landed class in Europe as evidence. Charitable giving at death squanders the talents of the wealth creators to deploy the capital effectively. This leaves the third option: “giving while living.” Carnegie argues powerfully that the highest use of wealth is philanthropic giving during one’s lifetime. He points to Peter Cooper’s Cooper Union and Samuel Tilden’s gift to create the New York Public Library as the ultimate examples of advancing the public good. These institutions were formed to spread the gift of knowledge to those who will use it to help themselves and others, creating a powerful multiplier effect (a common theme in effective philanthropy that we discuss further in this article). He appeals to the capital allocation acumen of wealth creators. They should focus their philanthropy on opportunities with the highest return on investment – those initiatives “best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community.”

We struggle to argue with Carnegie’s forceful logic. His philosophy has deeply influenced some of the greatest philanthropists of our generation, including Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. So if philanthropy is as clear a charge as Carnegie makes it out to be, why do so many approach it with hesitation? The answers are a combination of an inherent skepticism about the effectiveness of giving, lack of time, and a natural inclination to postpone confronting basic questions inherent in one’s philanthropy.

The not-for-profit sector has a poor reputation for achieving results. Perhaps more than anyone, those who have generated their wealth from the investment business expect to see a significant positive return on their investment in the form of demonstrable positive impact. Christopher Oechsli, the President and CEO of Atlantic Philanthropies (Charles Feeney’s foundation), sums it up by observing that “it is often much more difficult to invest private wealth to achieve effective and sustained improvements in society than it is to earn the wealth. And it is this challenge that keeps some wealthy people from engaging in philanthropy at all.”

Learning from Tom Tierney and the Bridgespan Group

Bridgespan was co-founded by and is led by a former Bain colleague and friend, Tom Tierney. Tom has been kind enough to lend his expertise to us. Tom offered a wealth of learning across hundreds of client engagements, which I have summarised below as a list of key lessons learned from his many years of advising wealthy individuals on what he refers to as the “upstream issues,” i.e., starting with a charitable purpose or a defined difference they want to make in the world. This is not Tom’s list, but rather my paraphrasing of the key takeaways from our discussion.

- One’s non-profit or philanthropic giving legacy is likely to be greater than one’s “working legacy.”

- “Giving while living” creates higher social impact than creating a foundation in perpetuity.

- There is an overwhelming amount of inertia with a tremendous propensity to delay this critical decision to a point where the individual has limited time left to make a difference while still living. The implication is, don’t delay.

- In philanthropy, excellence is self-imposed. There are no real market forces to guide and incent outstanding philanthropy; in fact, feedback loops tend to be highly distorted.

- Collaborate with others. Often people make the leap more comfortably with peers, friends or family members contributing money and/or time with them.

- Plant a few philanthropic seeds, and watch them grow, before deciding on the primary focus. Start with three, get a report card on results, focus on one.

- Philanthropy usually takes place across a portfolio of investments (gifts) including giving back to institutions (e.g., alma mater) and ad hoc contributions to those who ask, BUT one’s philanthropic legacy will only be fulfilled through highly strategic multi-year commitments.

- Invest time, and money follows.

- An important success pattern is around “big bets.” Donors who achieve outstanding results tend to pursue over time a handful of substantial strategic philanthropic efforts (“fewer, bigger, longer”).

Tom’s lessons seemed to be summarized by the old adage “a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” Too many of us are looking for the big win from the outset and worry about setting down the wrong path. Start small across two or three fronts, and get involved.

The bulk of Bridgespan’s efforts are not spent on these upstream issues, but rather the downstream strategic issues of deploying capital to have maximum impact especially around “big bets”: seeking to mitigate philanthropy’s “natural state of underperformance” as Tom puts it. Impact is effected by the choice of specific cause, the level of strategic clarity, the effectiveness of the people involved, and the ability to measure progress and adapt as necessary. Tom and other leading thinkers on philanthropy focus on “the multiplier effect” or getting a leveraged set of results for each dollar invested. We discuss the multiplier effect towards the end of this document in the section on specific action recommendations.

Social Impact Investing

Sir Ronald Cohen is a long time shareholder in our firm and has contributed hugely to our success over the years. Sir Ronald co-founded Apax Partners in 1972 and is known as “the father of British venture capital”. He is perhaps prouder to be known as “the father of social impact investment.” Social impact investment is the use of repayable finance to achieve a social as well as a financial return. It not only financially supports initiatives designed for a positive social outcome, it also harnesses the innovation capabilities of private entrepreneurs to develop effective and efficient programs aimed at social problems.

Sir Ronald has co-founded several successful social investment organizations, including Bridges Ventures, the Portland Trust, Social Finance, and Big Society Capital. Bridges Ventures is now the largest impact investment manager, with a billion dollars under management. Social Finance developed the social impact bond (SIB), where the financial return is tied to measurable success in improving social outcomes. The first SIB was targeted at reducing the rate of recidivism (re-offending) among male inmates in the UK, with the British government paying a share of the savings from the success of the program up to a maximum return of 13%.

Social impact investing could be the long overdue solution for the problem we are trying to solve here with this newsletter. To the extent our inertia in making the transition from investor to philanthropist is fueled by our mistrust of the charity world’s ability to deploy capital effectively and efficiently, social impact investing may be a powerful solution for wealthy investment professionals looking for the catalyst for making the transition to philanthropist.

Impact investing has seen rampant growth, and that growth is expected to continue. Approximately $50 billion was allocated to impact investing in 2009, and that number is expected to grow to $500 billion by 2019.

Jeff Raikes, the former CEO of the Gates Foundation, observed at a recent conference on the topic of impact investing that “the business model of philanthropy is being disrupted [by impact investing]. Philanthropy is moving from simple donations and grants to adding asset allocation from endowments to impact investment and commitments to pay for outcomes achieved.” In many ways this shift is creating its own multiplier effect on philanthropic funds as they can be recycled over and over again rather than spent once and gone. The more forward thinking donors to foundations look for institutions that are shifting from giving to investing for impact or they are investing themselves directly with impact investing programs.

In many ways, a philanthropy strategy that is based on investing for impact rather than giving away capital in hopes of impact plays to the skills of wealthy individuals who have gained their wealth as business leaders and investors. Regardless of what the principal cause or impact is that you are most passionate about achieving during your lifetime, your capital should be able to be deployed in ways that see both the return of your capital and a return in the form of a measurable social impact.

Leading Philanthropist Examples: Turning Passions into Purpose

Like Sir Ronald, many of our clients have successfully transitioned from spending to giving in meaningful ways. In this article, we have captured the learning not only from our clients, but also from some of the most thoughtful philanthropists, many of whom are from the investment world, applying business and investment principles to their approaches. We refer you to two excellent websites profiling well known philanthropists:

- Inside Philanthropy: Under “GrantFinder” you can find a list of technology and Wall Street donors with descriptions of their giving philosophies. See: http://www.insidephilanthropy.com/find-a-grant/

- The Chronicle of Philanthropy: Under “America’s Top Donors” you can search a database of major philanthropic gifts made in the last 10 years, with filters for the donor’s source of wealth and industry affiliation. See: https://philanthropy.com/factfile/gifts

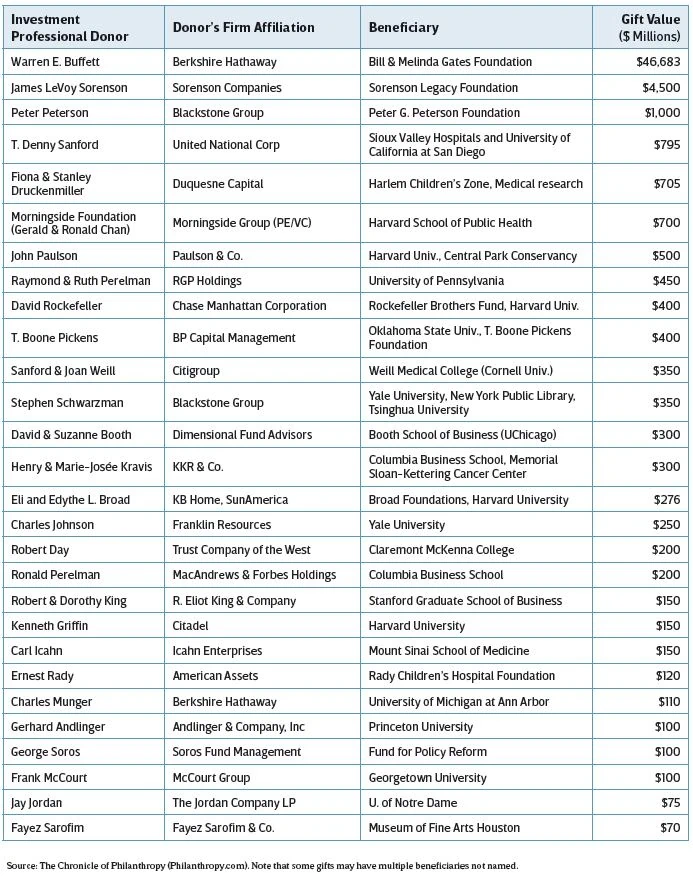

We find inspiration and creativity in the efforts of a number of investment professionals and technology entrepreneurs who have clearly identified what their passions are and then defied the challenges of philanthropy and made a clear positive impact on the world. They bring clear business thinking and processes to philanthropy in ways that are having a measurable impact on social and environmental causes in the world. All their efforts started with a deeply personal dedication to a cause – whether to help underprivileged people, to advocate for scientific progress or to promote a philosophy about the world. They have aligned their personal dedication with great people and organizations designed to deliver the greatest impact on their chosen causes. Below we share profiles of some of the best examples of making a difference that we have seen. We also include a list of some of the largest philanthropic gifts made by investment professionals in recent years, shown in Appendix 1. Below, we summarize examples of where personal passions have been directed with capital and effort to have a meaningful impact by ten of the world’s leading philanthropists coming out of the business, technology and investment world.

1. Bill Gates

Bill co-founded the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 2000 and has made philanthropy his full-time job since 2006, when he stepped down from his full-time position at Microsoft. Perhaps the greatest multiplier effect in philanthropy ever generated was in 2010, when Bill Gates and Warren Buffet started the Giving Pledge, a campaign that encourages the wealthiest people in the world to give at least half their wealth to philanthropic causes and now has well over 100 signatories. Clear objectives with measurable results are a hallmark of the Gates Foundation’s giving. One of the Gates Foundation’s major initiatives is the Discovery & Translational Sciences program which aims to create and improve preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic interventions for infectious diseases that disproportionately affect developing countries. These diseases include malaria, polio, tuberculosis, pneumonia, gastrointestinal and diarrheal diseases, and HIV/AIDS.

2. Michael Bloomberg

Bloomberg is a major proponent of leveraging philanthropic dollars to affect policy change, citing a study by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy that “every dollar grant makers and other donors invested in policy and civic engagement provided a return of $115 in community benefit.” In every major area he supports, he invests in collaboration with local and state governments to maximize his impact, and works to create programs that are scalable, replicable, and economically sound. He believes in helping organizations develop their leadership, share best practices, and create rigorous metrics that can help them measure their success.

3. George Soros

Soros’s philanthropy has largely been shaped by his early years. Growing up under authoritarian rule, he has shown an unwavering commitment to democratic ideals. For more than three decades, his philanthropy has been centered on building vibrant and tolerant democracies. When Soros set up his first non-U.S. foundation in Hungary in 1984, most of its resources were spent on distributing photocopiers to universities, libraries, and civil society groups. The goal was to promote the free flow of information and ideas, a critical tool in weakening authoritarian regimes and transitioning toward democracy.

4. Peter Peterson (Lehman Brothers, Blackstone)

Pete carefully considered which causes would give him the most pleasure to tackle and decided that it was America’s spending and borrowing policies that he wanted to address. Peterson focuses his giving almost exclusively on economic policy research and advocacy. These awards tend to go to established think tanks from across the ideological spectrum, though Peterson is most focused on bi-partisan and non-partisan organizations.

5. Jim Simons (Renaissance Technologies hedge fund)

Jim’s wealth is deployed in philanthropic ways through the Paul Simons Foundation, named for his son who died at a young age in a cycling accident. Jim’s passion for math and science has become the basis for his efforts to make a difference as he personally meets with experts in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and seeks out the best individuals and programs to fund. The multiplier effect comes from the impact Jim sees from funding educators in the “hard science” fields. The best example of this is his Math for America (MƒA) program which is Jim’s pet project. Its mission is “to improve mathematics and science education in US public secondary schools by building a corps of outstanding STEM teachers and school leaders.” MƒA offers a range of teaching fellowships and professional development opportunities for STEM teachers at all levels of their careers. It has also contributed to legislation on public teaching and education and aims to be the STEM education model adopted nationwide.

6. Paul Tudor Jones (Tudor Investment Corporation)

Paul Tudor Jones is the founder and Chair of the Robin Hood Foundation, an organization whose mission is to fight poverty in New York City, and is mainly backed by hedge funds. Jones likes to keep his philanthropy close to home, and when he tackles a problem, he tends to come at it from a number of angles. His Robin Hood Foundation has been called a pioneer in venture philanthropy, embracing free market forces for social benefit. He was also one of the first to apply rigorous metrics to measure the effectiveness of the programs he supports, and has been known to quickly discard programs if they prove ineffective. The charter school Jones founded in Bedford Stuyvesant is the nation’s first all-boys charter school for grades K-8, and has consistently outperformed city and statewide averages in reading and math.

7. Ray Dalio (Founder of Bridgewater Associates)

A signatory to the Giving Pledge, Dalio donates to hundreds of nonprofits every year through the Dalio Foundation. He has been ramping up his giving significantly in recent years, putting an additional $400 million into his foundation in 2013, pushing its total assets to $842 million that year. Dalio’s interests include the environment, global development and disaster relief, and the New York and Connecticut communities, but the largest portion of his philanthropy goes toward transcendental meditation, mind/body wellness, and education.

8. Pierre Omidyar (Founder of eBay)

Pierre has been instrumental in developing a more entrepreneurial model of philanthropy. His efforts have earned him a Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy Award and led former president Bill Clinton to describe him as “the new face of philanthropy.” Pierre has been a philanthropic innovator and a powerful advocate for a variety of causes. Distinguishing between charity and philanthropy, he focuses on developing philanthropic teams that can create long-term transformational change. Economic development, and specifically microfinance, is the biggest single object of Omidyar’s philanthropy. He supports numerous organizations that provide micro-financing throughout the world, as well as organizations that provide micro-insurance and other financial instruments to underserved communities. Recently, Omidyar and the development agencies of four national governments Australia, the U.K., the U.S., and Sweden— partnered to establish the Global Innovation Fund. Together they will invest tens of millions of dollars in “social innovations that aim to improve the lives and opportunities of millions of people in the developing world.”

9. Chuck Feeney

Chuck generated his wealth from Duty Free Shoppers, which he co-founded in 1960. Chuck was deeply influenced by Andrew Carnegie and adopted a philosophy that he called “Giving While Living.” He founded The Atlantic Philanthropies in 1982 and transferred virtually all of his wealth to the foundation which has a limited life concluding grant making in 2016. General Atlantic, the great private equity firm, was formed to invest a large portion of the foundation’s funds. The Atlantic Philanthropies has been focused on helping the elderly, underprivileged children and youth and supporting human rights. They have leveraged their own funds by influencing governments and private donors to match their efforts. His inspiration to so many others, including Bill Gates, is the ultimate example of the multiplier effect of effective philanthropy.

10. John Paulson

Hedge fund legend Paulson has an approach which may not support our central thesis of choosing a purpose where personal passion and impact meet, but this story’s absence here would be noticed. In June of this year, Paulson made the largest single donation ever received by Harvard University in the form of a $400 million gift to the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (now named after Paulson). This gift is clearly intended to enhance the East Coast’s relevance to technological innovation, to rival Stanford’s impact on Silicon Valley. Author Malcolm Gladwell launched a “tweet attack” on the back of this donation questioning the degree to which this was truly needed by Harvard, with its $35 billion endowment. Paulson has also given more than $20 million to his undergraduate alma mater, New York University, $11 million to the Spence School and $4 million to the London School of Economics. But his purposes also extend into health with a $15 million donation to build a maternity hospital in Ecuador where his father was born and, in 2012, Paulson gave $100 million to the New York Central Park Conservancy where he apparently bikes and jogs every day. If there is a strategic thread, John’s would be that he seeks to make a difference close to home.

Finding Your Mission: Combine Your Passions, Your Talents and Where You Can Effectively Make a Difference

As Tom Tierney writes, “All philanthropy is personal.” Personal dedication and clarity is essential to accomplishing the mission and delivering outstanding social impact. This is where most philanthropy breaks down. Donors give to “do their share” or because they “can’t say no,” but the giving lacks a focused sense of purpose and a realistic strategy. In this article, we provide you with some tools and frameworks for beginning your own path to identifying a cause that motivates you deeply and personally.

There are also likely to be causes where you may be uniquely equipped to make a difference with your talent and experience. We would encourage you to seek out the expert advice of firms like Bridgespan and Smarter Give, who are dedicated to helping donors to define their mission and give in a way to deliver the greatest impact.

Primary Framework for Finding your Mission: Where Passion Meets Impact

- Look to your core values, beliefs and passions and create a long list of objectives or causes that reflect these (see table in Appendix 2 as a decision-tree).

- Narrow this to a short list by evaluating each option in terms of where your amount of capital to invest can be effective (relative to the weight of capital others are deploying) and where you and your family can, and are keen to spend the time to, influence outcomes.

- Look at those surviving options and look at which is likely to offer the highest ROI due to the multiplier effect (see the “multiplier effect” framework below).

Ideally, your mission should have the following characteristics:

- Your support will have a leveraged impact (look for the multiplier effect on your money).

- It is something that you care passionately about.

- You can get involved personally to help; it is so meaningful to you that you will make the time for it (if you are able).

- The cause is focused and the objectives are clearly defined, such that your impact can be measured.

- It passes the “but for” test: results would not happen “but for” your contributions. It is not already over-funded; your efforts will be evident.

The multiplier effect is not a new concept in philanthropy. The more thoughtful business-oriented givers have always looked for the highest return on their philanthropy dollar. To illustrate, giving money to a homeless person on the street has a giving to benefit ratio of say 1:1. If the donor funds a civic body that puts homeless people to work, that may have a multiplier effect of say 1:100. Another classic source of leverage on philanthropy is funding a small number of people with a skill that can help many – medicine and education being the classic examples. In many cases, the multiplier effect can be less than 1:1 where charities incur excessive cost and inefficiently allocate capital. From our research, we include other examples of the multiplier effect on philanthropy below:

- Find the best run non-profit organizations that understand the concept of leverage and measure their effectiveness against clear measures on results per dollar spent. Charity Navigator (www.charitynavigator.com) and CharityWatch (www.charitywatch.com) are two well-known evaluators of charity effectiveness that can provide input to your thinking, but should not be relied upon for final decisions.

- Examine impact investment opportunities where they are likely to be more effective in achieving positive social outcomes than conventional donations (http://www.socialimpactinvestment.org/).

- Funding the most effective and proven social entrepreneurs. The Draper Richards Kaplan Foundation is one of several able “venture philanthropists” who effectively use your capital to back social entrepreneurs who they have vetted and who they monitor after the capital has been dispersed.

- Invest in efforts to change government policy or public awareness and attitudes which are blockages to social change (healthcare, education, etc.).

- Matching funds. Many philanthropists are making their capital contributions contingent on contributions of others. A recent example was Bloomberg and Soros committing $60 million to the New York City Young Men’s Initiative which aids minority males. This donation was tied to the City of New York investing a similar amount.

- Improving the effectiveness of charities by investing in those who have the skills to effectively advise worthy charitable foundations (e.g., firms who find more effective leaders, improve processes, network the various influencers together and improve communications among them, etc.). Bridgespan is one example.

The three steps outlined in our Primary Framework above should sound simple, if not obvious. But working through this is paralyzing for most starting down the path. Once you have set aside the time, turn to our Appendix 2: Finding Your Philanthropic Mission, and write down your answers to the critical questions to get you started down the road of self-reflection that is required to identify your mission. Don’t force yourself to have the complete and final answer to your mission. Start by actively pursuing one or more initiatives that excite you. We thank Bridgespan for allowing us to use their “5 P’s” framework here. This appendix shows the recent trends in philanthropic spending across religion, education, health, human services, international affairs and the environment and provides a decisiontree for your journey, along with a long list of wellknown philanthropic foundations (Appendix 3) to help you test what resonates most.

Implementing your Strategy to achieve your Philanthropic Mission

Implementation is potentially easier than setting out the strategy to achieve your philanthropic mission. But, the implementation is also critical. There are essential tax planning considerations involved and decisions on how much of your personal time will be devoted to your cause. There are significant advantages in most tax jurisdictions for establishing a family foundation as opposed to simply making annual gifts directly to worthy approved charitable foundations. Appendix 5 lays out the advantages and disadvantages of starting a foundation for our US taxpaying clients. We thank Boston-based law firm, Hurwit and Associates, for their insights here.

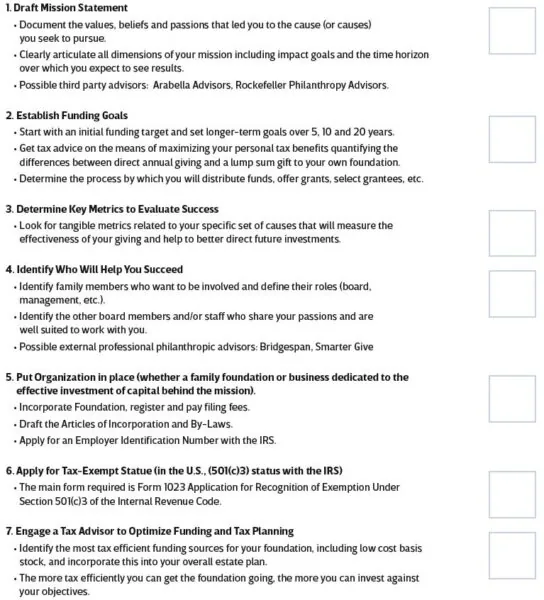

We have synthesized our overall learning on implementing a philanthropic mission from the leading thinkers into a simple set of seven steps in Appendix 4: Checklist of Actions for Implementing Your Philanthropic Mission. This should be helpful to get you started on this second phase of “making a difference.” Perhaps the key learning here is “what gets documented and measured has a better chance of getting done.” You should think of this as an outline for your business plan for “Making a Difference.”

When asked, experienced philanthropists always emphasize how rewarding they find their philanthropy. They find it fulfilling and fun…and advise others to “get going.”

We at Partners Capital are closely monitoring the evolution of philanthropy into impact investment. We believe that this may well herald a new era of investment where impact is added to the conventional investment dimensions of risk and return. As we go about investing your capital for the long-term (whether for you or your foundation), we hope that our foray into the world of philanthropy will help you on your journey into that challenging but essential universe.

Appendix 1: Example of Major Philanthropic Purposes from Investment Professionals

Appendix 2: Finding Your Philanthropic Mission

We have compiled a brief questionnaire to get you started on a short list of purposes and a hypothesis on

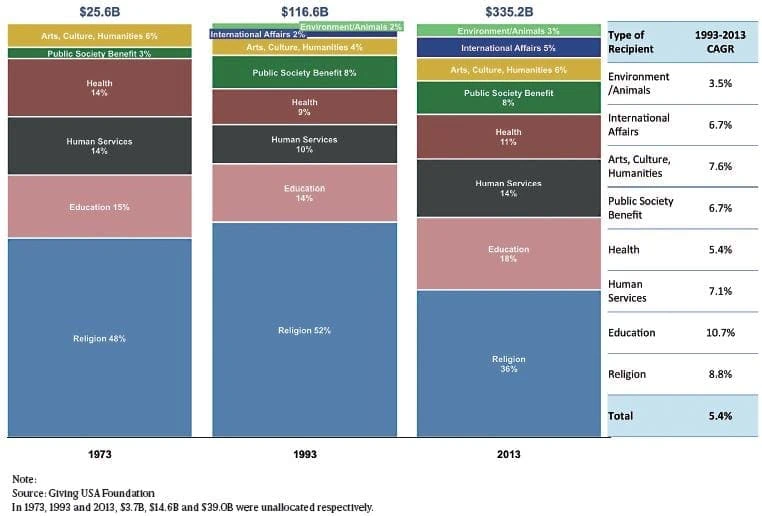

what is likely to be the center of your personal target for making a difference. As context, we provide below a summary of US philanthropic contributions by area over the last 40 years. While religion continues to attract over a third of all contributions, Education, Human services (providing food, shelter, clothing, etc.) and Health are the next largest beneficiaries and account for nearly half of all giving. Smaller, faster growing sectors include the Arts (5.6%), International Affairs (5%) and the Environment (3.3%).

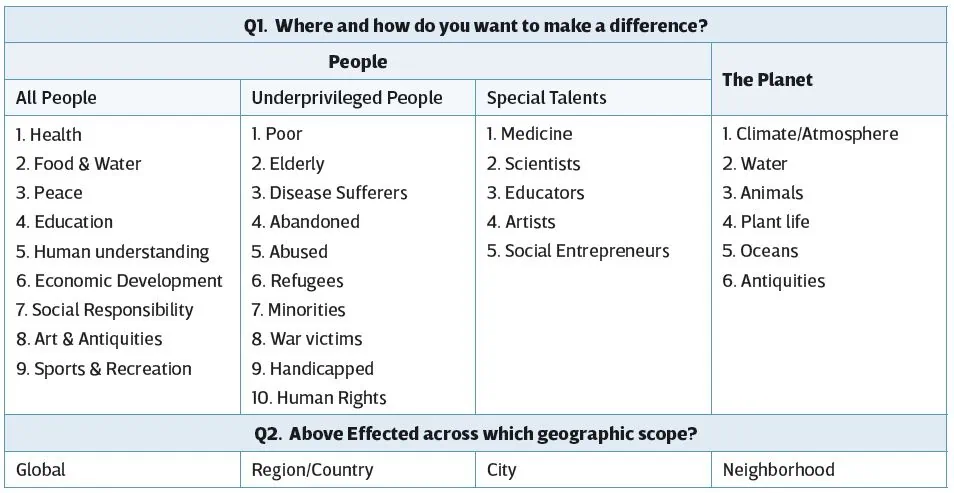

We have attempted to put together a simple decision tree in Figure 2 below that captures most of the causes or purposes of philanthropy at a high level before you drill down to define something more specific. This decision tree has you first choosing between helping a particular group of people or helping to improve the environment around us (“the planet”). The decision tree then goes on to question the desired geographic focus of your efforts. As we showed above, many philanthropists derive much greater satisfaction from making a difference close to home. But some purposes are inherently global.

Figure 1: Philanthropic Contributions by Type of Recipient (1973-2013)

Figure 2: Decision tree to get you started on Making a Difference

Next, think about your “anchors.” These are the core values that will define your giving choices. Bridgespan categorizes anchors into “Five Ps”:

- Values (Philosophy): defined by a viewpoint on how you think the world works or should work (e.g., promoting free markets or free speech, educating the public on the way the economy really works, etc.). What values in the world do you want to see preserved and encouraged?

- People you want to help: defined by a population and their unique circumstances (e.g., recidivism among inmates)

- Places you want to improve: defined by the health and vitality of a location (e.g., water shortages in California, schools in Ethiopia)

- Big Problems you want to solve: defined by a potential harm or obstacle to human or environmental well-being (e.g., extreme poverty and hunger, war-torn countries, etc.)

- Pathways: defined by a belief in a particular solution or approach (e.g., belief in a certain method of research or teaching, influencing government policy, bringing people together, etc.) These further three questions may help identify things you care a lot about not surfaced above.

- When you find yourself debating something passionately with the person next to you at a dinner party, what are those topics and is there a cause implied?

- If you were to take a year off work and dedicate your time to one philanthropic project, what would that be?

- What problem in the world, your country, your state or your city bothers you most?

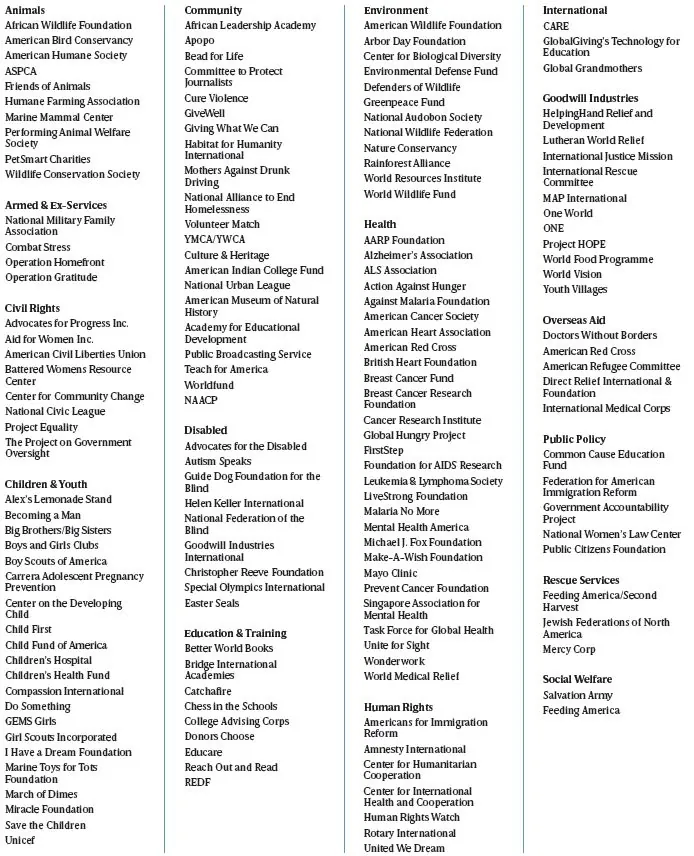

Appendix 3: Sample List of Leading Philanthropic Foundations

We provide this list as an additional catalyst for identifying causes that may be most meaningful to you.

Appendix 4: Checklist of Actions for Implementing Your Philanthropic Mission

Now that you have identified where you want to make a difference, you may decide to focus on investing with established foundations, start your own foundation or do a blend of both. Your foundation could be set up to work on the problem directly or to fund other organizations that are making a difference. Below are the key next steps for implementing your philanthropic mission. Use these as the key sections of your “Making a Difference” implementation plan.

Appendix 5: Advantages and Disadvantages of Setting up a US Foundation (Hurwit & Associates)

Advantages of Starting a Foundation

- Effective Philanthropy. The foundation vehicle may facilitate organized, systematic, and targeted giving.

- Expanded Giving Opportunities. Individuals may not claim charitable deductions for grants made to other individuals, foreign non-profit organizations, or non-charitable organizations. An individual, however, may achieve these expanded giving objectives by first making tax-deductible donations to a family foundation which may then in turn, once certain IRS procedures are followed, make such grants.

- Deductibility Plus Control. Donors may make tax-deductible donations to their own family foundation and still, as foundation trustees, remain in control of the investment and management of the funds as well the final charitable disposition of the gifts.

- Sheltered Income Plus Control. Foundation investment income, held by the foundation’s trustees, is exempt from taxation (with the exception of the 1-2% excise tax described below).

- Consistency in Giving. Under normal circumstances, foundations may accumulate and hold a portion of their funds. Foundations may also choose if and when to distribute such accumulated funds (or the income earned on accumulations). Thus, even though yearly contributions to the foundation may vary, giving levels are able to remain constant. Such consistency may be particularly helpful to grantees that rely on level funding from year to year.

- Payment of Reasonable Compensation. Under normal circumstances, family members and others may receive reasonable compensation from the foundation in return for services rendered.

- Reimbursement of Travel and Other Expenses. Reasonable and direct costs of site visits and board meetings may be paid by the foundation to family members, employees, and trustees.

- Double Capital Gains Tax Benefits. First, no capital gain is realized when appreciated property is donated to a foundation. Second, donors may claim a charitable deduction for the full market value of appreciated stock held in publicly traded companies.

- Estate Tax Reduction. Assets transferred to family foundations are generally not subject to estate taxes. This may provide triple tax savings when combined with the benefits above.

- Public and Community Relations. If desired, foundation grant making may bring recognition to family members.

- Privacy Concerns. On the other hand, individuals who are already subject to continuous fundraising appeals and interruptions at home and work may wish to increase their privacy by referring all such inquiries to the family foundation.

Disadvantages of Starting a Foundation

- Initial Time Commitment and Costs, including legal and accounting fees.

- Excise Tax. Private foundations are subject to a 1-2% annual excise tax on net income depending on the level of grant making from year to year. The tax, ostensibly, defrays the costs incurred by the government in regulating private foundations.

- Recordkeeping Requirements. At a minimum, family foundations should properly document grants and keep regular meeting minutes, which for small foundations may require an investment of 2-6 hours per grant-making cycle.

- Regulatory Requirements. There are two main classes of tax-exempt charitable organizations: public charities (funded by a variety of public sources) and private foundations (privately funded or endowed). Private foundations are required to distribute at least 5% of their net investment assets annually in the form of charitable grants and are subject to tighter scrutiny than public charities.

- Annual Reporting Requirements. Tax filings required by the IRS and most states typically require 4-8 hours to complete each year by an accountant or attorney.

- Lower Deductibility Caps. Individuals may receive tax deductions for donations to public charities to the extent of 50% of their adjusted gross income (AGI) for cash gifts and 30% of AGI for gifts of appreciated property. For gifts to private foundations, however, the limits are 30% of AGI for cash gifts and 20% of AGI for appreciated property.

- Less Favorable Treatment of Some Capital Gain Gifts. Gifts to public charities of appreciated property are deductible at fair market value. To private foundations, gifts of appreciated property are deductible on a cost basis only (with the exception of publicly traded stock which is deductible at fair market value).